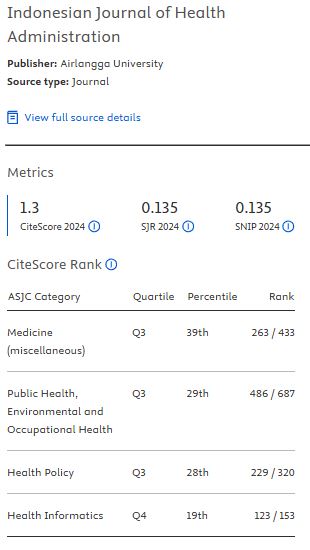

THE IMPLEMENTATION OF PATIENT SAFETY GOALS FOR PATIENTS' SATISFACTION IN THE HEMODIALYSIS UNIT

Background: Surveys on patient safety in dialysis units uncover a range of significant patient safety issues. Hemodialysis centers are particularly vulnerable to adverse events due to a number of risk factors, such as machine malfunctions, excessive blood loss, patient falls, prescription errors, and inadequate infection control procedures.

Aim: Analyze the problem of implementing patient safety goals and describe the patients' satisfaction with the implementation of patient safety goals.

Methods: This study employs a concurrent embedded methodology with a mixed-methods design, utilizing quantitative data to complement the qualitative data. Applying the focus group discussion (FGD) technique, questionnaires and observations of hemodialysis patients' satisfaction with implementing patient safety goals were utilized to complete the data collection.

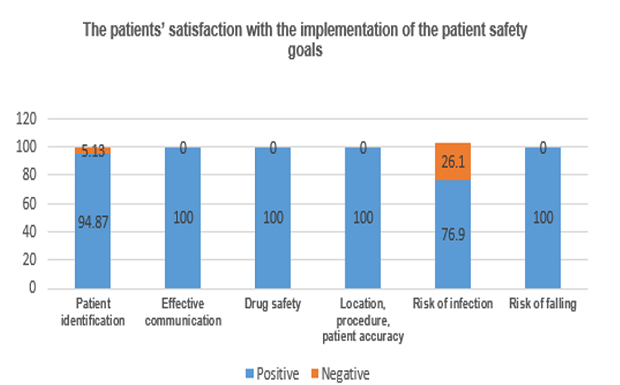

Results: According to the patient satisfaction survey, two patients were worried that their dialyzer tubes had been mixed up, earning a negative score of 5.13%. 23.07% of patients had negative results on the infection prevention risk questionnaire; 3 patients (7.69%) only seldom cleaned their hands before starting dialysis, and 6 patients (15.38%) did not.

Conclusion: The implementation of patients' identification and the reduction of infection risk through hand hygiene have not been carried out consistently, concerning patient safety goals in the hemodialysis unit.

Keywords: hand hygiene, hemodialysis, patient safety goals, patients' satisfaction, patients' identification

Introduction

Patient safety has gained significant international attention ever since the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published the results of its study conducted in the United States in 2000. According to a "To Err Is Human" study, there were 6.6% of fatalities and 2.9% of adverse events in Colorado and Utah. In New York, the incidence rate was 3.7% and the mortality rate was 13.6%(Yasmi & Thabrany, 2018). The unexpected event rate in hospitals in many different countries was discovered to vary between 3.2% and 16.6%. In Europe, 83.5% of patients faced an infection risk. Between 50% and 72.3% of patients had some indications of medical errors(Isnainy et al., 2021).

In 25 studies conducted in 27 countries across six continents, the average adverse events were reported at 10%, about a half (51.2%) were preventable, and 7.3% were fatal(Schwendimann & , 2018). It has been reported that the accurate patient safety measures may reduce healthcare- associated infections up to 70% across the United States of America(Lancet, 2019). The 313 outpatient records, exhibiting the highest treatment demand, contained 15.3% of the cases of adverse events. Procedure-related adverse events accounted for the majority (39.5%), treatments (21.9%), infections (10%), and diagnoses (0.1%)(Ortner & , 2021).

Hemodialysis centers are particularly vulnerable to adverse events due to a number of risk factors, such as machine malfunctions, excessive blood loss, patient falls, prescription errors, and inadequate infection control procedures. According to surveys on patient safety, there are numerous serious problems with patient safety in hemodialysis. Some studies conducted in four hemodialysis units in the United States discovered that 88 side effects occurred during 64,541 dialysis treatments in 17 months, or one case for every 733 treatments(Paula Faria Rocha, 2022).

Numerous studies outline the goals for patient safety in hemodialysis rooms. Patient identification and tube labeling are the two processes that pose the biggest risk to patient safety. These studies show that incorrect patient identification happens in 16.1% of cases and that inadequate labeling practices are responsible for 56% of patient misidentifications(Cornes & , 2019). Other research found that hemodialysis patients older than 65 had a 47% chance of falling within a year. This number exceeds the non-dialysis senior population's annual rate of 0.3–0.7 falls per patient(Paula Faria Rocha, 2022). Implementing patient’s safety goals is one-way hospitals can adopt to improve the quality of their medical care. The six patients’ safety goals as follows: lowering the risk of infection associated with health measures; improving and effective communication; increasing medicine safety; ensuring precise location, exact procedures, and exact patient during surgery; and lowering the risk of patient falls. Hospitals can evaluate patients’ safety goals and practices to identify and address safety issues that are relevant to day-to-day operations in hemodialysis units. In this study, the patients’ satisfaction related to the implementation of patients’ safety goals will be further examined, as will the issue of implementing patients’ safety goals in the hemodialysis unit.

Method

In this study, a concurrent embedding approach with a mixed method design is utilized, in which the quantitative and the qualitative data are combined simultaneously. The study was conducted in a type D private-public hospital with 45 patients on average and 390 hemodialysis treatments per month.

The seven nurses who work in the hemodialysis unit were observed during the qualitative data collection process, which also included Focus Group Discussion (FGD). Regarding the issues with patients’ safety goals, the implementation of FGD using the six patients’ safety goals was also discussed.

In order to gather quantitative data from 17- point questionnaires on patients' satisfaction with the implementation of their safety goals, a purposive sampling technique was applied to 45 patients, resulting in 39 hemodialysis patients with stable general conditions. The scale runs from 1 (not satisfied) to 4 (very satisfied). The qualities of tangible, responsiveness, assurance, empathy, and dependability are included in the patient satisfaction questionnaire. The objective of the questionnaires is to investigate how satisfied patients are with how the six patient safety goals have been implemented. Positive responses to the questionnaires are those that indicate high levels of satisfaction or contentment; negative responses indicate lower levels of satisfaction or dissatisfaction. The six patient safety goals were referenced in the questionnaire itemsFigure 1

Result and Discussion

The aforementionedTable 1andTable 2show the attributes of the respondents. The majority of hemodialysis patients who responded to the survey were female (46,15%), between the ages of 61 and 75 (51,28%), with a senior high school (41,02%), employed as farmers (30,77%), and receiving hemodialysis twice a week (92,31%).

The seven participants in the focus group discussion (FGD) were all nurses employed in the hemodialysis unit. Surveys regarding the overall experience were given to the 39 hemodialysis patients. All patients (100%) and the 26 patients (74.36%) who accompanied by their families are funded by the social security administrative agency (BPJS). All on-duty nurses on the hemodialysis unit were informed about the implementation of the patient safety goals during the Focus Group Discussion (FGD).

Figure 1.Questions about patient satisfaction with the implementation of patient safety goals

Characteristic | Variable | \( \documentclass{article} \usepackage{amsmath} \begin{document} \displaystyle n \end{document} \) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Gender | Male | 2 | 28,57 |

| Female | 5 | 71,43 | |

Education | Diploma | 7 | 100 |

Hemodialysis training | Own | 6 | 85,71 |

| Do not have | 1 | 14,79 |

Characteristic | Variable | \( \documentclass{article} \usepackage{amsmath} \begin{document} \displaystyle |

|---|

Al-Anazi, S. et al. (2022) ‘Compliance with hand hygiene practices among nursing staff in secondary healthcare hospitals in Kuwait', BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), p. 1325. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08706-8.

Cornes, M. et al. (2019) ‘Blood sampling guidelines with focus on patient safety and identification – a review', Diagnosis, 6(1), pp. 33–37. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2018-0042.

D´ Acunto, J.I. et al. (2021) ‘Detección de fallas en las pulseras identificatorias de pacientes internados', Medicina (Buenos Aires), 81(4), pp. 597–601. Available at: http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S0025-76802021000400597&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es.

De Paula Faria Rocha, R. (2022) ‘Patient Safety in Hemodialysis', in A. C.F. Nunes (ed.) Multidisciplinary Experiences in Renal Replacement Therapy. IntechOpen. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.101706.

Hammerschmidt, J. and Manser, T. (2019) ‘Nurses' knowledge, behaviour and compliance concerning hand hygiene in nursing homes: a cross-sectional mixed-methods study', BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), p. 547. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4347-z.

Hemesath, M.P. et al. (2015) ‘Educational strategies to improve adherence to patient identification', Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem, 36(4), pp. 43–48. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-1447.2015.04.54289.

Iffah, N., Anies, A. and Setyaningsih, Y. (2021) ‘Penerapan Keselamatan dan Kesehatan Kerja di Instalasi Hemodialisis Rumah Sakit', HIGEIA (Journal of Public Health Research and Development), 5(1), pp. 84–96. Available at: https://doi.org/10.15294/higeia.v5i1.39776.

Indrayadi, I., Oktavia, N.A. and Agustini, M. (2022) ‘Perawat dan Keselamatan Pasien: Studi Tinjauan Literatur', Jurnal Kepemimpinan dan Manajemen Keperawatan, 5(1), pp. 62–75. Available at: https://doi.org/10.32584/jkmk.v5i1.1465.

Isnainy, U.C.A.S., Gunawan, M.R. and Anjarsari, R. (2021) ‘Hubungan sikap perawat dengan penerapan patient safety pada masa pandemi Covid 19', Holistik Jurnal Kesehatan, 14(4), pp. 674–679. Available at: https://doi.org/10.33024/hjk.v14i4.3850.

Kusumastuti, D., Hilman, O. and Dewi, A. (2021) ‘Persepsi Pasien dan Perawat tentang Patient Safety di Pelayanan Hemodialisa', Jurnal Keperawatan Silampari, 4(2), pp. 526–536. Available at: https://doi.org/10.31539/jks.v4i2.1974.

Li, L. et al. (2022) ‘Assessment of the invisible blood contamination on nurses' gloved hands during vascular access procedures in a hemodialysis unit', American Journal of Infection Control, 50(6), pp. 712–713. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2021.12.009.

Ortner, J. et al. (2021) ‘Frequency of outpatient care adverse events in an occupational mutual insurance company in Spain', Journal of Healthcare Quality Research, 36(6), pp. 340–344. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhqr.2021.05.005.

Pratiwi, I.A. (2019) ‘Implementasi Sasaran Keselamatan Pasien di Rumah Sakit', Jurnal Akbid Griya Husada, 2(1), pp. 132–136.

Riplinger, L., Piera-Jiménez, J. and Dooling, J.P. (2020) ‘Patient Identification Techniques – Approaches, Implications, and Findings', Yearbook of Medical Informatics, 29(01), pp. 081–086. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1701984.

Schwendimann, R. et al. (2018) ‘The occurrence, types, consequences and preventability of in-hospital adverse events – a scoping review', BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), p. 521. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3335-z.

Surbakti, M.B. (2020) ‘Isu Terkini Terkait Keselamatan Pasien dan Keselamatan Kesehatan Kerja dalam Keperawatan'. Available at: https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/ys5q7.

The Lancet (2019) ‘Patient safety: too little, but not too late', The Lancet, 394(10202), p. 895. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32080-X.

Yasmi, Y. and Thabrany, H. (2018) ‘Faktor-Faktor Yang Berhubungan Dengan Budaya Keselamatan Pasien Di Rumah Sakit Karya Bhakti Pratiwi Bogor Tahun 2015', Jurnal Administrasi Rumah Sakit Indonesia, 4(2). Available at: https://doi.org/10.7454/arsi.v4i2.2563.

Copyright (c) 2024 Dwi Ambarwati, Arlina Dewi

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

1. As an author you (or your employer or institution) may do the following:

- make copies (print or electronic) of the article for your own personal use, including for your own classroom teaching use;

- make copies and distribute such copies (including through e-mail) of the article to research colleagues, for the personal use by such colleagues (but not commercially or systematically, e.g. via an e-mail list or list server);

- present the article at a meeting or conference and to distribute copies of the article to the delegates attending such meeting;

- for your employer, if the article is a ‘work for hire', made within the scope of your employment, your employer may use all or part of the information in the article for other intra-company use (e.g. training);

- retain patent and trademark rights and rights to any process, procedure, or article of manufacture described in the article;

- include the article in full or in part in a thesis or dissertation (provided that this is not to be published commercially);

- use the article or any part thereof in a printed compilation of your works, such as collected writings or lecture notes (subsequent to publication of the article in the journal); and prepare other derivative works, to extend the article into book-length form, or to otherwise re-use portions or excerpts in other works, with full acknowledgement of its original publication in the journal;

- may reproduce or authorize others to reproduce the article, material extracted from the article, or derivative works for the author's personal use or for company use, provided that the source and the copyright notice are indicated.

All copies, print or electronic, or other use of the paper or article must include the appropriate bibliographic citation for the article's publication in the journal.

2. Requests from third parties

Although authors are permitted to re-use all or portions of the article in other works, this does not include granting third-party requests for reprinting, republishing, or other types of re-use.

3. Author Online Use

- Personal Servers. Authors and/or their employers shall have the right to post the accepted version of articles pre-print version of the article, or revised personal version of the final text of the article (to reflect changes made in the peer review and editing process) on their own personal servers or the servers of their institutions or employers without permission from JAKI;

- Classroom or Internal Training Use. An author is expressly permitted to post any portion of the accepted version of his/her own articles on the author's personal web site or the servers of the author's institution or company in connection with the author's teaching, training, or work responsibilities, provided that the appropriate copyright, credit, and reuse notices appear prominently with the posted material. Examples of permitted uses are lecture materials, course packs, e-reserves, conference presentations, or in-house training courses;