ANTI-SMOKING MESSAGES VERSUS PRO-SMOKING MESSAGES AMONG INDONESIAN ADOLESCENT SMOKERS

Background: Anti-smoking messages (ASM) is a program designed to educate the public about the dangers of tobacco use, aiming to prevent adolescents and young people from smoking cigarettes in any form and to assist smokers in giving up their smoking habit. On the contrary, pro-smoking messages (PSM) is a marketing technique to promote tobacco products.

Aims: This study was conducted to describe the exposure to ASM and PSM among Indonesian adolescent smokers (IAS).

Methods: This study analyzed secondary data from the 2019 Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) Indonesia. The outcome variable was the respondent's smoking intensity in the last 30 days. The independent variables were the exposure to ASM and PSM in the various below-the-line media.

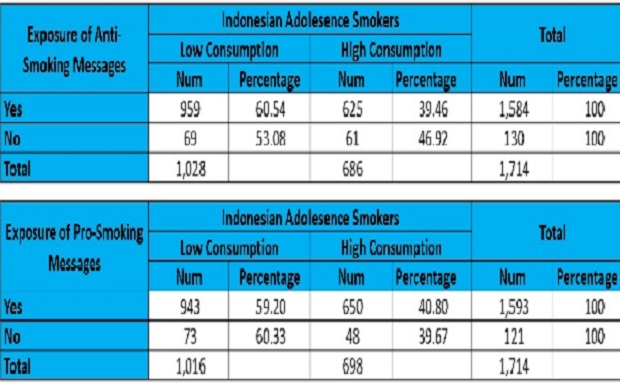

Results: Most IAS were male (93.4%), mostly in secondary school (60.3%) and spent more than IDR 11,000 per week (71.1%). Adolescent smokers were exposed to ASM at a rate of 92.4%. Furthermore, ASM exposure happened to 60.5% of the low-intensity youth smoker group and 39.5% of the high-intensity youth smoker group. Meanwhile, 93% of adolescent smokers were exposed to PSM, with 40.8% in the high-intensity youth smoker group and 59.2% in the low-intensity youth smoker group.

Conclusion: The exposure to ASM and PSM in the adolescent smoker group was relatively the same.

Keywords: ASM, PSM, prevention, public health, tobacco control, youth

Introduction

One of the leading causes of death globally is tobacco usage. There is growing apprehension regarding the susceptibility of adolescents to tobacco addiction(W.H.O., 2021). Adolescents between the ages of 13 and 15 years make up 25 million of the world's cigarette consumers. The Southeast Asia Region (SEARO) and Western Pacific Region (WPRO) showed the highest prevalence of smoking with an estimated 6.4 million and 4.7 million individuals affected, respectively. Indonesia significantly contributes to the prevalence of smoking throughout its regions(Lian & Dorotheo, 2021).

Tobacco smoke comprises a vast array of over 4,000 distinct chemical compounds, 40 of which have carcinogenic properties. The presence of carbon monoxide, tar, nicotine, and heavy metals in tobacco smoke at elevated levels can lead to the development of cardiovascular disease, oral and lung cancer, diminished respiratory function, and impaired fertility(Lian & Dorotheo, 2021).

Numerous studies have provided substantial evidence suggesting that the initiation of smoking during adolescence causes immediate detrimental impacts on health and raises the risk of serious illnesses throughout one’s lifespan(U.S.D.H.S.S., 2012). The initiation of cigarette smoking during adolescence can result in nicotine dependence, hence exerting detrimental effects on the long-term development of the brain. In addition, it is important to note that those who engage in smoking at a young age face potential consequences such as the deceleration of lung function and delayed lung development(U.S.D.H.S.S., 2014).

Anti-smoking messages (ASM) programs play a vital role in disseminating knowledge to the general population regarding the hazards associated with tobacco consumption. These initiatives serve to prevent adolescents and young individuals from initiating cigarette smoking in any manifestation, while also providing support to smokers to stop smoking(Andersen et al., 2018). Contrarily, pro- smoking messages (PSM) function as a marketing strategy utilized by the tobacco industry to endorse its products, primarily focusing on attracting younger audiences(U.S.D.H.S.S., 2012).

Previous studies have addressed the correlation between ASM and PSM and youth smoking behavior. Numerous studies have examined the impact of anti-tobacco media on the decrease or prevention of tobacco use in adolescents(Emory & , 2015);(Erguder & , 2013). Other studies on anti-tobacco media have focused on anti-smoking campaigns and the prevailing smoking rates to develop impactful interventions to mitigate the prevalence of smoking(Rao & , 2014). Additional evidence can be found in a study conducted by Mannocci et al. (2021), which revealed that adolescents exhibit a preference for anti-smoking messages that include a scientific orientation and effectively challenge misconceptions about smoking(Mannocci & , 2019).

On the other hand, several studies have also shown an association between PSM and youth smoking behavior. PSM can be defined as a combination of direct and indirect marketing strategies through the sponsorship of athletic events and music festivals, which involve the use of billboards and ads(U.S.D.H.S.S., 2012). Existing studies have unequivocally demonstrated a correlation between adolescent smoking patterns and the promotion of tobacco products through advertisements(Agaku et al., 2014);(Megatsari & , 2019);(Shang & , 2016). Therefore, this study aims to describe the exposure to ASM and PSM among Indonesian adolescent smokers (IAS).

Method

The 2019 Indonesian Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) was a cross- sectional study conducted at Indonesia's public and private schools to investigate the prevalence of tobacco use among students aged from 13 to 17 years.

The authors acquired the data for the 2019 Indonesia Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) from the official website of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC):https://www.gtssacademy.org/explore/datase ts/.

Sampling in this study was divided into two distinct phases. In the initial phase, schools were selected using the probability-proportionate-to-size (PPS) method. The subsequent phase involved the random selection of courses from various educational institutions. A comprehensive survey was conducted among the entire student population of the selected classes.

The data collection method was initiated by the enumerators through a brief chat with the teacher and administration team at the school. During this interaction, the enumerators explained the sample class, and thereafter, all students in the selected class actively participated in the survey. The interview was conducted with all students enrolled in the designated class, with an approximate duration of 45 minutes.

Before disseminating the questionnaire to the students, the enumerators provided a comprehensive explanation of the protocols and guidelines for completing the answer sheets and the questionnaire. Before participating in the survey, students were required to provide consent. Data collected were generally about the response choices provided by each student. Upon the completion of all the questions, the research team proceeded with data collection from the answer sheets.

The dependent variable in this study was the smoking consumption level reported by the respondents within the past 30 days. For the categorization, the consumption was considered low if the respondent smoked less than one cigarette per day, while high consumption was defined as consuming two cigarettes or more than two cigarettes per day. The study examined ASM and PSM exposure across a range of existing media platforms, including television, radio, internet, billboards, posters, newspapers, magazines, and movies throughout a 30- day timeframe. The other variables were sex (male and female), grade (secondary school and high school), and weekly spending money categories (I usually don’t have any spending money, less than IDR 11,000, IDR 11,000-20.000, IDR 21,000-30.000, IDR 31,000-40.000, IDR 41,000-50.000, and more than IDR 50.000).

Agaku, I.T., King, B.A. and Dube, S.R. (2014) ‘Trends in exposure to pro-tobacco advertisements over the Internet, in newspapers/magazines, and at retail stores among U.S. middle and high school students, 2000–2012', Preventive Medicine, 58, pp. 45–52. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.10.012.

Andersen, S. et al. (2018) Best Practices User Guide: Health Communications in Tobacco Prevention and Control. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

Astuti, P.A.S. and Freeman, B. (2017) ‘"It is merely a paper tiger.” Battle for increased tobacco advertising regulation in Indonesia: content analysis of news articles', BMJ Open, 7(9), p. e016975. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016975.

Asyary, A. et al. (2021) ‘Prevalence of Smoke-Free Zone Compliance among Schools in Indonesia: A Nationwide Representative Survey', Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP, 22(2), pp. 359–363. Available at: https://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2021.22.2.359.

Bayly, M., Cotter, T. and Carroll, T. (2019) ‘Examining the effectiveness of public education campaigns', in M. Scollo and M. Winstanley (eds) Tobacco in Australia: Facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria. Available at: https://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-14-social-marketing/14-4-examining-effectiveness-of-public-education-c.

Beasley, S. et al. (2020) ‘What makes an effective antismoking campaign – insights from the trenches', Public Health Research & Practice, 30(3). Available at: https://doi.org/10.17061/phrp3032021.

Dubray, J. et al. (2014) ‘The effect of MPOWER on smoking prevalence', Tobacco Control, 24(6), pp. 540–542. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051834.

Efendi, F. et al. (2019) ‘Determinants of smoking behavior among young males in rural Indonesia', International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 33(5). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2019-0040.

Emory, K.T. et al. (2015) ‘Receptivity to cigarette and tobacco control messages and adolescent smoking initiation', Tobacco control. 2014/02/06 edn, 24(3), pp. 281–284. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051187.

Erguder, T. et al. (2013) ‘Exposure to anti- and pro-tobacco advertising, promotions or sponsorships: Turkey, 2008', Global Health Promotion, 23(2_suppl), pp. 58–67. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975913502369.

GCGGTC (2023) How Deadly Is Tobacco Industry Influence in Indonesia? Bangkok, pp. 15. Available at: https://globaltobaccoindex.org/country/ID.

Gentzke, A.S. et al. (2020) ‘Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students - United States, 2020', MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 69(50), pp. 1881–1888. Available at: https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6950a1.

Heydari, G. (2020) ‘A decade after introducing WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, trend analysis of implementation of the WHO FCTC MPOWER in Eastern Mediterranean Region', in. Tobacco, smoking control and health educ., European Respiratory Society. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.congress-2020.3041.

Heydari, Gh. et al. (2013) ‘WHO MPOWER tobacco control scores in the Eastern Mediterranean countries based on the 2011 report', Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 19(04), pp. 314–319. Available at: https://doi.org/10.26719/2013.19.4.314.

Kemp, S. (2021) DIGITAL 2021: INDONESIA, Data Reportal. Available at: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-indonesia.

KPAI (2017) ‘Tanpa Kompromi, KPAI Minta UU Penyiaran Cantumkan Larangan Iklan Rokok', KPAI Publikasi, pp. 3–3. Available at: https://www.kpai.go.id/publikasi/tanpa-kompromi-kpai-minta-uu-penyiaran-cantumkan-larangan-iklan-rokok.

Laili, K. et al. (2022) ‘The impact of exposure to cigarette advertising and promotion on youth smoking behavior in Malang Regency (Indonesia) during the COVID- 19 Pandemic', Journal of public health in Africa, 13(Suppl 2), pp. 2409–2409. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4081/jphia.2022.2409.

Lian, T.Y. and Dorotheo, U. (2021) The Tobacco Control Atlas: ASEAN Region. 5th edn. Edited by B. Ritthiphakdee et al. Bangkok: Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance (SEATCA), p. 188. Available at: https://seatca.org/dmdocuments/SEATCA ASEAN Tobacco Control Atlas_5th Ed.pdf.

Maharani, D. (2016) ‘Iklan Antirokok Terbaru Fokus Bahaya Rokok Pada Organ', Kompas.com, pp. 2–2. Available at: https://health.kompas.com/read/2016/09/02/152417023/iklan.antirokok.terbaru.fokus.bahaya.rokok.pada.organ.

Mannocci, A. et al. (2019) ‘Which are the communication styles of anti-tobacco spots that most impress adolescents?', European Journal of Public Health, 29(Supplement_4). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz185.114.

Megatsari, H. et al. (2019) ‘Visibility and hotspots of outdoor tobacco advertisement around educational facilities without an advertising ban: Geospatial analysis in Surabaya City, Indonesia', Tobacco prevention & cessation, 5, pp. 32–32. Available at: https://doi.org/10.18332/tpc/112462.

MKRI (2017) ‘Petition on Review of Cigarette Advertising Rejected', Constitutional Court of the Republic of Indonesia, pp. 2–2. Available at: https://en.mkri.id/news/details/2017-12-14/Petition_on_Review_of_Cigarette_Advertising_Rejected.

MOH-RI (2015) Pesan dari Korban Rokok (Ibu Ike), Youtube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xFGvm3HqOt8.

MOH-RI (2019) National Result of Basic Health Research in Indonesia for the Period of 2018 (Riskesdas 2018). Jakarta: Ministry of Health of Republic of Indonesia.

Ngo, A. et al. (2017) ‘The effect of MPOWER scores on cigarette smoking prevalence and consumption', Preventive medicine. 2017/05/11 edn, 105S, pp. S10–S14. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.05.006.

Prabandari, Y.S. and Dewi, A. (2016) ‘How do Indonesian youth perceive cigarette advertising? A cross-sectional study among Indonesian high school students', Global health action, 9, pp. 30914–30914. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v9.30914.

Primasari, S.I. and Listina, F. (2022) ‘Faktor Faktor Yang Berhubungan dengan Kepatuhan Dalam Penerapan Kawasan Tanpa Rokok Di Lingkungan Puskesmas Candipuro Kabupaten Lampung Selatan', Jurnal Ilmu Kesehatan Indonesia (JIKSI), 2(2). Available at: https://doi.org/10.57084/jiksi.v2i2.737.

Ramadhan, L.I. (2016) ‘Iklan Antirokok Kemenkes dari Kisah Nyata di Muara Angke', Tempo.co, pp. 2–2. Available at: https://nasional.tempo.co/read/774674/iklan-antirokok-kemenkes-dari-kisah-nyata-di-muara-angke.

Rao, S. et al. (2014) ‘Anti-smoking initiatives and current smoking among 19,643 adolescents in South Asia: findings from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey', Harm reduction journal, 11, pp. 8–8. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-11-8.

Sadeghi, R., Masoudi, M.R. and Khanjani, N. (2020) ‘A Systematic Review about Educational Campaigns on Smoking Cessation', The Open Public Health Journal, 13(1), pp. 748–755. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2174/1874944502013010748.

Septiono, W. et al. (2021) ‘Self-reported exposure of Indonesian adolescents to online and offline tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship (TAPS)', Tobacco Control, 31(1), pp. 98–105. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056080.

Shang, C. et al. (2016) ‘Global Evidence on the Association between POS Advertising Bans and Youth Smoking Participation', International journal of environmental research and public health, 13(3), p. 306. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13030306.

Soerojo, W. et al. (2020) Atlas Tembakau Indonesia 2020. Jakarta, Republic of Indonesia, pp. 33–33. Available at: https://www.tcsc-indonesia.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Atlas-Tembakau-Indonesia-2020.pdf.

Sutrisno, R.Y. and Melinda, F. (2021) ‘The Effects of Cigarette Advertisement and Peer Influence on Adolescent's Smoking Intention in Indonesia', Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences, 9(T4), pp. 291–295. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2021.5809.

USDHSS (2012) Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), p. 80. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99237/.

USDHSS (2014) The Health Consequences of Smoking”50 Years of Progress. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), p. 192. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276/.

WHO (2008) MPOWER: A Policy Package to Reverse the Tobacco Epidemic, WHO. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.who.int/blindness/AP2014_19_Russian.pdf?ua=1.

WHO (2021) WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2021 Addressing New and Emerging Products. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/343287/9789240032095-eng.pdf?sequence=1%26isAllowed=y.

WHO (2023) WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2023: Protect People from Tobacco Smoke. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/372043/9789240077164-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

Copyright (c) 2024 Hario Megatsari, Rita Damayanti, Dian Kusuma, Mursyidul Ibad, Siti Rahayu Nadhiroh, Erni Astutik, Susy Katikana Sebayang

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

1. As an author you (or your employer or institution) may do the following:

- make copies (print or electronic) of the article for your own personal use, including for your own classroom teaching use;

- make copies and distribute such copies (including through e-mail) of the article to research colleagues, for the personal use by such colleagues (but not commercially or systematically, e.g. via an e-mail list or list server);

- present the article at a meeting or conference and to distribute copies of the article to the delegates attending such meeting;

- for your employer, if the article is a ‘work for hire', made within the scope of your employment, your employer may use all or part of the information in the article for other intra-company use (e.g. training);

- retain patent and trademark rights and rights to any process, procedure, or article of manufacture described in the article;

- include the article in full or in part in a thesis or dissertation (provided that this is not to be published commercially);

- use the article or any part thereof in a printed compilation of your works, such as collected writings or lecture notes (subsequent to publication of the article in the journal); and prepare other derivative works, to extend the article into book-length form, or to otherwise re-use portions or excerpts in other works, with full acknowledgement of its original publication in the journal;

- may reproduce or authorize others to reproduce the article, material extracted from the article, or derivative works for the author's personal use or for company use, provided that the source and the copyright notice are indicated.

All copies, print or electronic, or other use of the paper or article must include the appropriate bibliographic citation for the article's publication in the journal.

2. Requests from third parties

Although authors are permitted to re-use all or portions of the article in other works, this does not include granting third-party requests for reprinting, republishing, or other types of re-use.

3. Author Online Use

- Personal Servers. Authors and/or their employers shall have the right to post the accepted version of articles pre-print version of the article, or revised personal version of the final text of the article (to reflect changes made in the peer review and editing process) on their own personal servers or the servers of their institutions or employers without permission from JAKI;

- Classroom or Internal Training Use. An author is expressly permitted to post any portion of the accepted version of his/her own articles on the author's personal web site or the servers of the author's institution or company in connection with the author's teaching, training, or work responsibilities, provided that the appropriate copyright, credit, and reuse notices appear prominently with the posted material. Examples of permitted uses are lecture materials, course packs, e-reserves, conference presentations, or in-house training courses;