COST-ANALYSIS OF REDUCING MORTALITY RATE FOR LBW BABIES AT FATMAWATI HOSPITAL'S NICU

Background: As a developing country that still struggles with infant mortality, Indonesia needs high-quality and efficient neonatal care. However, due to the complexity of neonatal care, the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) still has a high cost, approximately USD 950 - 31,000, as the last line of care.

Aims: This study analyzes the cost incurred due to service improvement at Fatmawati General Hospital. The cost analysis may serve as useful evidence for other hospitals with NICUs that seek to improve their service.

Methods: We used cost analysis to examine pre-intervention costs in 2015 and post-intervention costs in 2021. Our data were gathered primarily in the NICU of Fatmawati General Hospital for three months in 2023.

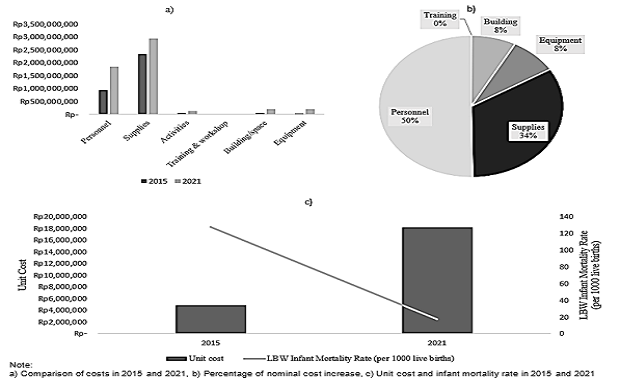

Results: The results showed an increase in total cost of IDR 1,898,040,489 (55%). The largest cost increase was personnel and supplies costs, which accounted for 83.8% of the cost increase. However, this cost increase was also followed by a significant decrease in mortality rates, from 128 deaths per 1,000 births to 17 deaths per 1,000 births.

Conclusion: This study found a correlation between investment in service improvements and decreased infant mortality rates in the NICU of Fatmawati General Hospital. Although the 55% increase in total cost was associated with a significant decrease in infant mortality rates in the NICU of Fatmawati General Hospital, further studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of improvements in the NICU's services.

Keywords: cost, Indonesia, LBW, NICU

Introduction

Infant health and well-being issues are being addressed globally. Goal 3.2 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) states that one of its goals is to reduce preventable deaths of newborns to as low as 12 per 1,000 live births by 2030(Nations, 2023). As of 2021, Indonesia’s infant mortality rate remained at 19 per 1,000 live births, even after Indonesia regained its status as an upper middle-income country(Finance, 2023);(U.N.I.C.E.F., 2023).

According to data for three consecutive years from the Indonesian Ministry of Health, LBW/ prematurity was the main cause of infant mortality, and the figure was around 27% annuallyTable 1. Premature birth occurs when a baby is born before completing 37 weeks of gestation. The more premature a baby is, the greater the risk of mortality and morbidity. Premature babies may experience breathing difficulties, digestive problems, bleeding in the brain, and may have long- term effects such as stunted growth during

childhood(C.D.C., 2022).

Causes of Death | Incidence | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

LBW | 27.33% | 27.76% | 27.60% |

Asphyxia | 20.42% | 21.63% | 22.19% |

| Congenital | 9.95% | 8.97% | 12.36% |

As the last line of neonatal care, where premature infants with complications are usually cared for, a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is one of the more expensive forms of care.(Sharma & Murki, 2021)made a summary of NICU costs from a literature study of various studies related to cost analysis in the NICU while(Karambelkar et al., 2016)examined 126 neonates in India who were treated in the NICU for various diseases. It is estimated that approximately USD 90.7 is spent every day for care in the NICU.(Narang et al., 2005)showed that the expenditure for each baby admitted to the NICU has several classifications. For extreme low birth weight (ELBW) babies, it is around 3,800 USD, for babies between 1,000g and 1,250g, it is approximately USD 2,000, and for babies between 1,250g and 1500g, it is around USD 950(Narang et al., 2005). Meanwhile,(Kirkby & , 2007)found that the average cost for each preterm infant admitted to the NICU is USD 31,000.

Although it is difficult to make a balanced comparison for each costing study of the NICU, it can be concluded that managing a neonatal unit has significant costs. The complexity of neonatal unit management can be attributed to the high nurse/patient ratio and high expertise needed to solve neonatal problems(Sharma & Murki, 2021). With all the complexities and difference, and costly NICU treatments in multiple countries, it is important for Indonesia to have publications on NICU costs. To the best of our knowledge, no literature has discussed the empirical cost of NICU in Indonesia.

In addition to infants’ early complications, their underdeveloped immune system makes them at greater risk of infection. Unfortunately, infection can sometimes occur during hospitalization, which is called healthcare associated infections (HAIs). The impact of HAIs can be morbidity, mortality, or financial burden to various stakeholders such as patients, their families, and the country's healthcare system(Sikora & Zahra, 2022). The US Center for Disease Control and Prevention states that, every year, nearly 1.7 million treated patients develop HAIs, and more than 98,000 of them die from HAIs. The prevalence of HAIs documented in the data shows that approximately 3.2% of all US patients and 6.5% of all patients in the European Union are affected by HAIs, and even higher rates worldwide(Allegranzi & , 2011);(Magill & , 2018);(Suetens & , 2018).

The occurrence rate of HAIs in the neonatal intensive care unit is around 30%, and 40% of neonatal deaths in developing countries are due to such infections(Pessoa"Silva & , 2004);(Zaidi & , 2005). There are several reasons why HAIs are increasingly dangerous, with hospitals hosting more patients with weakened immune systems. In addition, with the outpatient system, the risk for pathogen spread is higher. Sanitation protocols are lacking, and sterilization of equipment by medical staff is not strict. Widespread use of anti-microbial drugs also has a negative impact due to accumulation of anti- microbial resistance. Increased infections are associated with longer hospital length of stay, long-term disability, socioeconomic disruption, and increased mortality(Khan et al., 2017). In addition, newborns admitted to the NICU are at risk for HAIs due to their physiologic instability, exposure to invasive medical equipment, and broad-spectrum antibiotics(N.N.I.S., 2004);(Singh, 2004);(Sohn & , 2001). Infection rates in NICUs are also higher than those in well-baby nurseries, with infection rates in NICUs ranging from 6 to 40 per 100 admissions, while infection rates in well-baby nurseries range from 0.3 to 1.7 per 100 admissions(Scheckler & Peterson, 1986);(Welliver & Mclaughlin, 1984).

Neonatal care is a difficult and expensive domain to implement. If not managed properly, the effectiveness and efficiency of the NICU can be questioned and can place a significant financial burden on healthcare budgets. The high cost in NICUs also makes many hospitals management reluctant to invest in NICUs, especially in the treatment of LBW babies. Therefore, a cost analysis study is needed to provide evidence of the cost of improving NICU service and the extent to which infant mortality rates have changed. Furthermore, we aim to provide evidence for other hospitals with NICUs that also seek to

Allegranzi, B. et al. (2011) ‘Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis', The Lancet, 377(9761), pp. 228–241. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61458-4.

Anwar, Z. and Butt, T.K. (2009) ‘Cost of patient care in neonatal unit', Pakistan Paediatric Journal, 33(1), pp. 14–18. Available at: https://pakmedinet.com/14343.

CDC (2022) ‘Premature Birth. Reproductive Health'. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/features/premature-birth/index.html.

Drummond, M.F. et al. (2015) Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. (Oxford University Press).

Helle, E. et al. (2016) ‘Morbidity and Health Care Costs After Early Term Birth', Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 30(6), pp. 533–540. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/ppe.12321.

Indonesian Ministry of Finance (2023) Recent Macroeconomics and Fiscal Update. Indonesian Ministry of Finance.

Karambelkar, G., Malwade, S. and Karambelkar, R. (2016) ‘Cost-analysis of healthcare in a private-sector neonatal intensive care unit in India', Indian Pediatrics, 53(9), pp. 793–795. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-016-0933-x.

Khan, H.A., Baig, F.K. and Mehboob, R. (2017) ‘Nosocomial infections: Epidemiology, prevention, control and surveillance', Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine, 7(5), pp. 478–482. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apjtb.2017.01.019.

Kirkby, S. et al. (2007) ‘Clinical outcomes and cost of the moderately preterm infant', Advances in Neonatal Care, 7(2), pp. 80–87. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ANC.0000267913.58726.f3.

Magill, S.S. et al. (2018) ‘Changes in Prevalence of Health Care–Associated Infections in U.S. Hospitals', New England Journal of Medicine, 379(18), pp. 1732–1744. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1801550.

McLaurin, K.K. et al. (2009) ‘Persistence of morbidity and cost differences between late-preterm and term infants during the first year of life', Pediatrics, 123(2), pp. 653–659. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-1439.

Narang, A., Kiran, P.S.S. and Kumar, P. (2005) ‘Cost of neonatal intensive care in a tertiary care center', Indian Pediatrics, 42(10), pp. 989–997. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16269829/.

NNIS (2004) ‘National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Report, data summary from January 1992 through June 2004, issued October 2004', American Journal of Infection Control, 32(8), pp. 470–485. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2004.10.001.

Pessoa"Silva, C.L. et al. (2004) ‘Healthcare"Associated Infections Among Neonates in Brazil', Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 25(9), pp. 772–777. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.66.7.696.

Scheckler, W.E. and Peterson, P.J. (1986) ‘Nosocomial infections in 15 rural Wisconsin hospitals - Results and conclusions from 6 months of comprehensive surveillance', Infection Control, 7(8), pp. 397–402. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0195941700064626.

Sharma, D. and Murki, S. (2021) ‘Making neonatal intensive care: cost effective', Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, 34(14), pp. 2375–2383. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2019.1660767.

Sikora, A. and Zahra, F. (2022) Nosocomial infections. (StatPearls Publishing). Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32644738/.

Singh, N. (2004) ‘Large Infection Problems in Small Patients Merit a Renewed Emphasis on Prevention', Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 25(9), pp. 714–718. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1086/502465.

Sohn, A.H. et al. (2001) ‘Prevalence of nosocomial infections in neonatal intensive care unit patients: Results from the first national point-prevalence survey', Journal of Pediatrics, 139(6), pp. 821–827. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1067/mpd.2001.119442.

Suetens, C. et al. (2018) ‘Prevalence of healthcare-associated infections, estimated incidence and composite antimicrobial resistance index in acute care hospitals and long-term care facilities: Results from two european point prevalence surveys, 2016 to 2017', Eurosurveillance, 23(46), pp. 1–18. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.46.1800516.

UNICEF (2023) ‘Indonesia (IDN) - Demographics, Health & Infant Mortality - UNICEF DATA'. Available at: https://data.unicef.org/country/idn/.

United Nations (2023) Goal 3. Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3.

Welliver, R.C. and Mclaughlin, S. (1984) ‘Unique Epidemiology of Nosocomial Infection in a Children's Hospital', American Journal of Diseases of Children, 138(2), pp. 131–135. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1984.02140400017004.

Zaidi, A.K.M. et al. (2005) ‘Hospital-acquired neonatal infections in developing countries', Lancet, 365(9465), pp. 1175–1188. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71881-X.

Copyright (c) 2024 Prasetya Rahman Salim, Nadia Dwi Insani, Estro Dariatno Sihaloho

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

1. As an author you (or your employer or institution) may do the following:

- make copies (print or electronic) of the article for your own personal use, including for your own classroom teaching use;

- make copies and distribute such copies (including through e-mail) of the article to research colleagues, for the personal use by such colleagues (but not commercially or systematically, e.g. via an e-mail list or list server);

- present the article at a meeting or conference and to distribute copies of the article to the delegates attending such meeting;

- for your employer, if the article is a ‘work for hire', made within the scope of your employment, your employer may use all or part of the information in the article for other intra-company use (e.g. training);

- retain patent and trademark rights and rights to any process, procedure, or article of manufacture described in the article;

- include the article in full or in part in a thesis or dissertation (provided that this is not to be published commercially);

- use the article or any part thereof in a printed compilation of your works, such as collected writings or lecture notes (subsequent to publication of the article in the journal); and prepare other derivative works, to extend the article into book-length form, or to otherwise re-use portions or excerpts in other works, with full acknowledgement of its original publication in the journal;

- may reproduce or authorize others to reproduce the article, material extracted from the article, or derivative works for the author's personal use or for company use, provided that the source and the copyright notice are indicated.

All copies, print or electronic, or other use of the paper or article must include the appropriate bibliographic citation for the article's publication in the journal.

2. Requests from third parties

Although authors are permitted to re-use all or portions of the article in other works, this does not include granting third-party requests for reprinting, republishing, or other types of re-use.

3. Author Online Use

- Personal Servers. Authors and/or their employers shall have the right to post the accepted version of articles pre-print version of the article, or revised personal version of the final text of the article (to reflect changes made in the peer review and editing process) on their own personal servers or the servers of their institutions or employers without permission from JAKI;

- Classroom or Internal Training Use. An author is expressly permitted to post any portion of the accepted version of his/her own articles on the author's personal web site or the servers of the author's institution or company in connection with the author's teaching, training, or work responsibilities, provided that the appropriate copyright, credit, and reuse notices appear prominently with the posted material. Examples of permitted uses are lecture materials, course packs, e-reserves, conference presentations, or in-house training courses;