Main Article Content

Abstract

Highlights:

- The post-mortem interval is related to tryptase and chymase expressions in anaphylactic shock incidence

- Forensic experts can utilize tryptase and chymase as markers of anaphylactic (non-anaphylactoid) shock that occurs in the lungs.

Abstract:

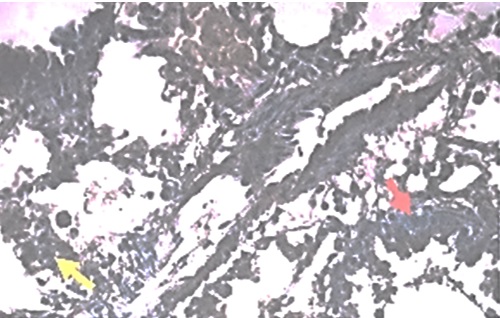

Anaphylactic shock is a hypersensitivity response, a commonly type I hypersensitivity involving immunoglobulin E (IgE). It is caused by an antigen-antibody reaction that occurs immediately after a sensitive antigen enters the circulation. Anaphylactic shock is a clinical manifestation of anaphylaxis that is distributive shock, characterized by hypotension due to sudden blood vessel vasodilation and accompanied by a collapse in blood circulation that can result in death. β-tryptase and mast cell chymase expressions in the lungs of histopathological specimens that had experienced anaphylactic shock were examined at different post-mortem intervals in this study. A completely randomized design (CRD) method was employed by collecting lung samples every three hours within 24 hours of death, and then preparing histopathological and immunohistochemical preparations. The mast cell tryptase and chymase expressions were counted and summed up in each field of view, and the average was calculated to represent each field of view. The univariate analysis yielded p-values of 0.008 at the 15-hour post-mortem interval, and 0.002 at the 12-hour post-mortem interval. It was concluded that tryptase and chymase can be utilized as markers of anaphylactic (non-anaphylactoid) shock in the lungs.

Keywords

Article Details

Copyright (c) 2023 Folia Medica Indonesiana

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

-

Folia Medica Indonesiana is a scientific peer-reviewed article which freely available to be accessed, downloaded, and used for research purposes. Folia Medica Indonesiana (p-ISSN: 2541-1012; e-ISSN: 2528-2018) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Manuscripts submitted to Folia Medica Indonesiana are published under the terms of the Creative Commons License. The terms of the license are:

Attribution ” You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial ” You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

ShareAlike ” If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original.

No additional restrictions ” You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits.

You are free to :

Share ” copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format.

Adapt ” remix, transform, and build upon the material.

References

- Abbas M, Moussa M, Akel H (2022). Type I hypersensitivity reaction.

- Bayo MFA (2019). Perbedaan indeks apoptosis sel neuron cerebrum dan cerebellum mencit baru lahir pada kebuntingan remaja dan dewasa (thesis). Universitas Airlangga.

- Bosmans T, Melis S, De Rooster H, et al (2014). Anaphylaxis after intravenous administration of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid in two dogs under general anesthesia. Vlaams Diergeneeskundig Tijdschrift 83, 14–9. doi: 10.21825/vdt.v83i1.16671.

- Canova S, Cortinovis DL, Ambrogi F (2017). How to describe univariate data. Journal of Thoracic Disease 9, 1741–3. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.05.80.

- Choi JY, Kim JH, Han HJ (2019). Suspected anaphylactic shock associated with administration of tranexamic acid in a dog. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 81, 1522–6. doi: 10.1292/jvms.19-0225.

- Endaryanto A, Nugraha RA (2022). Safety profile and issues of subcutaneous immunotherapy in the treatment of children with allergic rhinitis. Cells 11, 1584. doi: 10.3390/cells11091584.

- Hanlon KE, Vanderah TW (2010). Constitutive activity in receptors and other proteins, Part A. Methods in Enzimology 484, 3-30.

- Hasanah APU, Baskoro A, Edwar PPM (2020). Profile of anaphylactic reaction in Surabaya from January 2014 to May 2018. JUXTA Jurnal Ilmiah Mahasiswa Kedokteran Universitas Airlangga 11, 61. doi: 10.20473/juxta.V11I22020.61-64.

- Isyroqiyyah NM, Soegiarto G, Setiawati Y (2021). Profile of drug hypersensitivity patients hospitalized in Dr. Soetomo Hospital, Surabaya, Indonesia: Preliminary data of 6 months observation. Folia Medica Indonesiana 55, 54. doi: 10.20473/fmi.v55i1.24387.

- Kounis N, Soufras G, Hahalis G (2013). Anaphylactic shock: Kounis hypersensitivity-associated syndrome seems to be the primary cause. North American Journal of Medical Sciences 5, 631. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.122304.

- McLendon K, Sternard BT. (2022). Anaphylaxis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls; 2022.

- Poziomkowska-Gęsicka I, Kurek M (2020). Clinical manifestations and causes of anaphylaxis. Analysis of 382 cases from the anaphylaxis registry in West Pomerania Province in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, 2787. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082787.

- Reber LL, Hernandez JD, Galli SJ (2017). The pathopysiology of anaphylaxis Journal of Allergy and Linical Immunology 140, 335-48. doi: 10.1016/j.jac.2017.06.003.

- Rengganis I (2016). Anafilaksis: Apa dan bagaimana pengobatannya? Divisi Alergi dan Imunologi Klinik, Departemen Penyakit Dalam, FK UI, Jakarta.

- Shinee T, Sutikno B, Abdullah B (2019). The use of biologics in children with allergic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis: Current updates. Pediatric Investigation 3, 165–72. doi: 10.1002/ped4.12146.

- Shmuel DL, Cortes Y (2013). Anaphylaxis in dogs and cats. Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care 23, 377–94. doi: 10.1111/vec.12066.

- Smith M (2015). Anaphylaxis, allergy, and the food factor in disease. In Another Person's Poison, 43–66. Columbia University Press.

- Stefanski AL, Raclawska DS, Evans CM (2018). Modulation of lung epithelial cell function using conditional and inducible transgenic approaches. In Methods in Molecular Biology, 169–201. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8570-8_14.

- Turner PJ, Jerschow E, Umasunthar T, et al (2017). Fatal anaphylaxis: Mortality rate and risk factors. The Journal of Allergy Clinical Immunology: In Practice 5, 1169–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.06.031.

- Yudhawati R, Krisdanti DPA (2019). Imunopatogenesis asma. Jurnal Respirasi 3, 26. doi: 10.20473/jr.v3-I.1.2017.26-33.

References

Abbas M, Moussa M, Akel H (2022). Type I hypersensitivity reaction.

Bayo MFA (2019). Perbedaan indeks apoptosis sel neuron cerebrum dan cerebellum mencit baru lahir pada kebuntingan remaja dan dewasa (thesis). Universitas Airlangga.

Bosmans T, Melis S, De Rooster H, et al (2014). Anaphylaxis after intravenous administration of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid in two dogs under general anesthesia. Vlaams Diergeneeskundig Tijdschrift 83, 14–9. doi: 10.21825/vdt.v83i1.16671.

Canova S, Cortinovis DL, Ambrogi F (2017). How to describe univariate data. Journal of Thoracic Disease 9, 1741–3. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.05.80.

Choi JY, Kim JH, Han HJ (2019). Suspected anaphylactic shock associated with administration of tranexamic acid in a dog. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 81, 1522–6. doi: 10.1292/jvms.19-0225.

Endaryanto A, Nugraha RA (2022). Safety profile and issues of subcutaneous immunotherapy in the treatment of children with allergic rhinitis. Cells 11, 1584. doi: 10.3390/cells11091584.

Hanlon KE, Vanderah TW (2010). Constitutive activity in receptors and other proteins, Part A. Methods in Enzimology 484, 3-30.

Hasanah APU, Baskoro A, Edwar PPM (2020). Profile of anaphylactic reaction in Surabaya from January 2014 to May 2018. JUXTA Jurnal Ilmiah Mahasiswa Kedokteran Universitas Airlangga 11, 61. doi: 10.20473/juxta.V11I22020.61-64.

Isyroqiyyah NM, Soegiarto G, Setiawati Y (2021). Profile of drug hypersensitivity patients hospitalized in Dr. Soetomo Hospital, Surabaya, Indonesia: Preliminary data of 6 months observation. Folia Medica Indonesiana 55, 54. doi: 10.20473/fmi.v55i1.24387.

Kounis N, Soufras G, Hahalis G (2013). Anaphylactic shock: Kounis hypersensitivity-associated syndrome seems to be the primary cause. North American Journal of Medical Sciences 5, 631. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.122304.

McLendon K, Sternard BT. (2022). Anaphylaxis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls; 2022.

Poziomkowska-Gęsicka I, Kurek M (2020). Clinical manifestations and causes of anaphylaxis. Analysis of 382 cases from the anaphylaxis registry in West Pomerania Province in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, 2787. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082787.

Reber LL, Hernandez JD, Galli SJ (2017). The pathopysiology of anaphylaxis Journal of Allergy and Linical Immunology 140, 335-48. doi: 10.1016/j.jac.2017.06.003.

Rengganis I (2016). Anafilaksis: Apa dan bagaimana pengobatannya? Divisi Alergi dan Imunologi Klinik, Departemen Penyakit Dalam, FK UI, Jakarta.

Shinee T, Sutikno B, Abdullah B (2019). The use of biologics in children with allergic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis: Current updates. Pediatric Investigation 3, 165–72. doi: 10.1002/ped4.12146.

Shmuel DL, Cortes Y (2013). Anaphylaxis in dogs and cats. Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care 23, 377–94. doi: 10.1111/vec.12066.

Smith M (2015). Anaphylaxis, allergy, and the food factor in disease. In Another Person's Poison, 43–66. Columbia University Press.

Stefanski AL, Raclawska DS, Evans CM (2018). Modulation of lung epithelial cell function using conditional and inducible transgenic approaches. In Methods in Molecular Biology, 169–201. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8570-8_14.

Turner PJ, Jerschow E, Umasunthar T, et al (2017). Fatal anaphylaxis: Mortality rate and risk factors. The Journal of Allergy Clinical Immunology: In Practice 5, 1169–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.06.031.

Yudhawati R, Krisdanti DPA (2019). Imunopatogenesis asma. Jurnal Respirasi 3, 26. doi: 10.20473/jr.v3-I.1.2017.26-33.