LYMPHATIC FILARIASIS DRUG TREATMENT POLICIES IN EASTERN INDONESIA: WHAT TARGET CHARACTERISTICS MATTER?

Background: Lymphatic filariasis (LF) drug treatment compliance remains a challenge in Eastern Indonesia.

Aims: The study sought to determine which aspects of Eastern Indonesia's LF drug treatment compliance policies were most pertinent.

Methods: The 2018 Indonesian Basic Health Survey data was employed. The analysis units were adults (≥ 15 years) who had received LF drug treatment. LF drug treatment compliance was analyzed based on respondent characteristics (age, gender, marital status, education, occupation, wealth and comorbidities) using binary logistic regression.

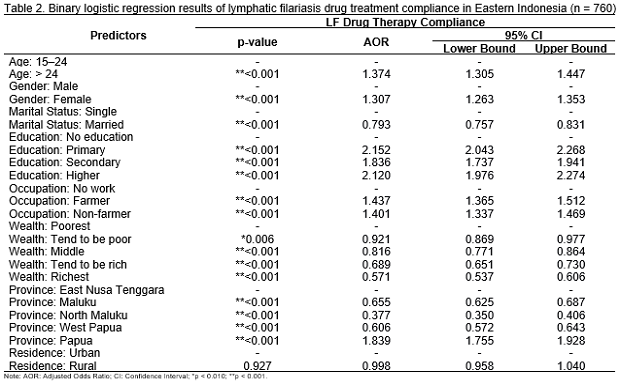

Results: The proportion of adherence to LF treatment in Eastern Indonesia was 73.1%. Respondent characteristics that influenced LF treatment compliance were age group > 24 (aOR = 1.374, 95% CI: 1.305-1.447), female (aOR = 1.307, 95% CI: 1.263-1.353), all educated respondent status (aOR = 2.152, 95% CI: 2.043-2.268), and all employed respondents (aOR = 1.437, 95% CI: 1.365 - 1.512). Married respondents and those with all levels of wealth status were less likely to take LF drug treatment.

Conclusion: Policy focus on improving LF treatment compliance among the younger male, the less educated, the unemployed, and those with lower social economic status.

Keywords: compliance, Eastern Indonesia, lymphatic filariasis, public health

Introduction

The neglected tropical disease lymphatic filariasis (LF) is caused by roundworms of the family Filariodidea carried by such mosquitoes as Aedes, Culex, Mansonia, and Anopheles. LF is not a fatal disease, but it can cause permanent disability(Lourens & Ferrell, 2019);(Sungpradit & Sanprasert, 2020). In 2020, there were 72 LF endemic countries, and 863 million individuals in 47 of these countries needed prophylactic chemotherapy to prevent LF. The disease is distributed in tropical and sub-tropical regions such as Africa, the South Pacific Islands, Southeast Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean(Sungpradit & Sanprasert, 2020). In 2000, the distribution of the highest prevalence of LF in the world was in Southeast Asia, with a 52% prevalence of LF worldwide. It was estimated that the majority of LF cases in 2018 would remain in Southeast Asia, including Indonesia, with the provinces of East Nusa Tenggara and Papua having the highest numbers of LF cases(N.I.H.R.D., 2019);(Deshpande & , 2020).

Efforts to prevent LF require the involvement of all sectors and stakeholders, with health promotion and knowledge improvement for the public being essential to LF risk reduction(Maryen et al., 2018). In addition, to break the chain of transmission, the government implements a mass drug administration (MDA) program in LF endemic areas. The procedure for MDA typically involves the distribution of medications. The use of community drug distributors, known as cadres in Indonesia, who collaborate with village health personnel to deliver LF medications, is one of the main elements of mass treatment programs in Indonesia(Titaley & , 2018). MDA coverage necessitates the population's willingness to take the drug as prescribed. Several places with limited resources have struggled to sustain MDA coverage over time(Won & , 2009);(Burgert-Brucker & , 2020). A number of prior studies have found that low MDA compliance for the elimination of LF is one of the variables determining the incidence of re-transmission of LF in locations that have completed MDA(Widjanarko et al., 2018);(Biritwum & , 2019);(Burgert-Brucker & , 2020).

Some obstacles to MDA adherence for the elimination of LF are related to individual influences and program implementation(Silumbwe & , 2017). Individual influences include fear of adverse events(Mathieu & , 2004);(Widiastuti & , 2021), education level(Kasturiratne & , 2001), occupation, knowledge(Krentel & , 2016)and wealth(Gunawardena & , 2007). One of the impacts of the program is increased participants' exposure to advertisements on the media as well as local drug distributors and health worker visits(Krentel & , 2016). Indonesia is an archipelago of approximately 260 million inhabitants(Bank, 2020). The dispersion of the population, the vast distances involved, and the geography of the region are obstacles for the population to receive expeditious treatment(Meireles & , 2020)and it is also true for Indonesia(Suharmiati et al., 2013);(Laksono et al., 2020). Based on the preceding information, this study aimed to identify the most suitable characteristics for LF drug treatment compliance policies in the eastern region of Indonesia. The findings of this research can be considered in the development of appropriate policies regarding targets related to MDA coverage to accelerate the elimination of LF in eastern Indonesia, including whether intensive socialization or involvement of key stakeholders is needed.

Method

Data Source

For this study, secondary data were taken from the 2018 Indonesian Basic Health Survey, carried out by the National Institute of Health Research and Development (NIHRD). Indonesia also conducted a community-based cross- sectional survey in 2018 as part of its Basic Health Survey. This survey's sample structure was derived from the results of the 2018 National Socio-economic Survey, which was carried out by the Central Statistics Agency in March of 2018. The 2018 Indonesian Basic Health Survey targeted 300,000 households from 30,000 census blocks, and the 2018 Indonesian Socio-economic Survey targeted 300,000 families from 30,000 census blocks.

The 2018 Indonesian Basic Health Survey adopted Probability Proportional to Size (PPS), a two-stage systematic linear sampling method. The first stage constituted implicit stratification based on the 2010 Population Census' determination of the welfare strata of each census unit. As many as 180,000 census blocks (or 25%) of the total 720,000 census blocks from the 2010 Population Census were chosen by PPS as the sampling frame from the sample survey. The survey counted census blocks in each urban/rural stratum per regency/city using the PPS method to create a census block sample list, resulting in 30,000 census blocks being surveyed. The second phase used systematic sampling to identify the ten homes in each census block with the highest implicit stratification of education completed by the head of household. Members of randomly chosen households in Indonesia were questioned for the 2018 Basic Health Survey(N.I.H.R.D., 2019).

Specifically, 295,720 houses in 34 provinces with 1,091,528 household members were surveyed for the 2018 Indonesia Basic Health Survey. A sample of data from five chosen provinces was studied. We limited our analysis to people aged 15 years and above (n = 790) living in five provinces (Papua \( \documentclass{article} \usepackage{amsmath} \begin{document} \displaystyle (n = 274) \end{document} \), West Papua \( \documentclass{article} \usepackage{amsmath} \begin{document} \displaystyle (n = 99) \end{document} \), Maluku \( \documentclass{article} \usepackage{amsmath} \begin{document} \displaystyle (n = 177) \end{document} \), North Maluku \( \documentclass{article} \usepackage{amsmath} \begin{document} \displaystyle (n = 50)

Agustini, A. and Indrawati, F. (2018) ‘Program Pemberian Obat Pencegahan Massal (POPM) Filariasis', Higeia Journal of Public Health Research and Development, 1(3), pp. 84–94. Available at: http://journal.unnes.ac.id/sju/index.php/higeia.

Biritwum, N.K. et al. (2019) ‘Progress towards lymphatic filariasis elimination in Ghana from 2000-2016: Analysis of microfilaria prevalence data from 430 communities', PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 13(8). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007115.

Boyd, A. et al. (2010) ‘A community-based study of factors associated with continuing transmission of lymphatic filariasis in Leogane, Haiti', PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 4(3), pp. 1–10. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000640.

Burgert-Brucker, C.R. et al. (2020) ‘Risk factors associated with failing pretransmission assessment surveys (Pre-tas) in lymphatic filariasis elimination programs: Results of a multi-country analysis', PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 14(6), pp. 1–17. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008301.

Deshpande, A. et al. (2020) ‘The global distribution of lymphatic filariasis, 2000–18: a geospatial analysis', The Lancet Global Health, 8(9), pp. e1186–e1194. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30286-2.

Dickson, B.F.R. et al. (2021) ‘Risk factors for lymphatic filariasis and mass drug administration non-participation in Mandalay Region, Myanmar', Parasites and Vectors, 14(1), pp. 1–14. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04583-y.

Durrheim, D.N. et al. (2004) ‘Editorial: Lymphatic filariasis endemicity – an indicator of poverty?', Tropical Medicine & International Health, 9(8), pp. 843–845. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1365-3156.2004.01287.X.

Gunawardena, G.S.A. et al. (2007) ‘Impact of the 2004 mass drug administration for the control of lymphatic filariasis, in urban and rural areas of the Western province of Sri Lanka', Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology, 101(4), pp. 335–341. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1179/136485907X176364.

Gunawardena, S. et al. (2007) ‘Factors influencing drug compliance in the mass drug administration programme against filariasis in the Western province of Sri Lanka', Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 101(5), pp. 445–453. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.09.002.

Ikawati, B. et al. (2019) ‘Supporting factors to get coverage of malaria mass blood survey (MBS) above 80%: Lesson learn from gripit village, Banjarmangu sub district, Banjarnegara district', Indian Journal of Public Health Research and Development, 10(3), pp. 649–653. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-5506.2019.00575.8.

Indonesia Ministry of Health (2020) Indonesia Health Profile. Jakarta: Indonesia Ministry of Health.

Inobaya, M.T. et al. (2018) ‘Mass drug administration and the sustainable control of schistosomiasis: Community health workers are vital for global elimination efforts', International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 66, pp. 14–21. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2017.10.023.

Ipa, M. et al. (2016) ‘Analysis of mass drug coverage for prevention of filariasis in Bandung district with a system dynamic model approach.', Balaba, 12(1), pp. 31–38. Available at: http://ejournal2.litbang.kemkes.go.id/index.php/blb/article/view/721.

Kasturiratne, K.T. et al. (2001) ‘Compliance with the mass chemotherapy program for lymphatic filariasis', The Ceylon Medical Journal, 46(4), pp. 126–129. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4038/cmj.v46i4.6431.

Kerjapy, S.L., Titaley, C.R. and Sanaky, M. (2019) ‘Faktor-faktor Penerimaan Obat Pada Program Pemberian Obat Pencegahan Massal (POPM)', Pattimura Medical Review, 1(1). Available at: https://ojs3.unpatti.ac.id/index.php/pameri/article/view/1279.

Kouassi, B.L. et al. (2018) ‘Perceptions, knowledge, attitudes and practices for the prevention and control of lymphatic filariasis in Conakry, Republic of Guinea', Acta Tropica, 179, pp. 109–116. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.12.002.

Koyadun, S. and Bhumiratana, A. (2005) ‘Surveillance of imported bancroftian filariasis after two-year multiple-dose diethylcarbamazine treatment', The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health, 36(4), pp. 822–831. Available at: https://www.thaiscience.info/journals/Article/TMPH/10594791.pdf.

Krentel, A. et al. (2016) ‘Improving Coverage and Compliance in Mass Drug Administration for the Elimination of LF in Two "Endgame” Districts in Indonesia Using Micronarrative Surveys', PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 10(11), pp. 1–22. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005027.

Krentel, A., Fischer, P.U. and Weil, G.J. (2013) ‘A Review of Factors That Influence Individual Compliance with Mass Drug Administration for Elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis', PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 7(11). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002447.

Kulkarni, P. et al. (2020) ‘Mass drug administration programme against lymphatic filariasis-an evaluation of coverage and compliance in a northern Karnataka district, India', More..., 8(1), pp. 87–90. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2019.04.013.

Laksono, A.D., Rukmini, R. and Wulandari, R.D. (2020) ‘Regional disparities in antenatal care utilization in Indonesia', PLoS ONE, 15(2), pp. e0224006–e0224006. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224006.

Lourens, G.B. and Ferrell, D.K. (2019) ‘Lymphatic Filariasis', Nursing Clinics of North America, 54(2), pp. 181–192. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2019.02.007.

Manyeh, A.K. et al. (2020) ‘Exploring factors affecting quality implementation of lymphatic filariasis mass drug administration in bole and central gonja districts in northern ghana', PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 14(8), pp. 12–23. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007009.

Manyeh, A.K. et al. (2021) ‘Evaluating context-specific evidence-based quality improvement intervention on lymphatic filariasis mass drug administration in Northern Ghana using the RE-AIM framework', Tropical Medicine and Health, 49(1), pp. 16–16. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-021-00305-3.

Maryen, Y., Kusnanto, H. and Indriani, C. (2018) ‘Risk Factors of Lymphatic Filariasis in Manokwari, West Papua', Tropical Medicine Journal, 4(1), pp. 60–64. Available at: https://journal.ugm.ac.id/tropmed/article/view/37186.

Mathieu, E. et al. (2004) ‘Factors associated with participation in a campaign of mass treatment against lymphatic filariasis, in Leogane, Haiti', Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology, 98(7), pp. 703–714. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1179/000349804X3135.

Meireles, B.M. et al. (2020) ‘Factors associated with malaria in indigenous populations: A retrospective study from 2007 to 2016', PLOS ONE. Edited by J. Moreira, 15(10), p. e0240741. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240741.

Nandha, B. et al. (2007) ‘Delivery strategy of mass annual single dose DEC administration to eliminate lymphatic filariasis in the urban areas of Pondicherry, South India: 5 years of experience', Filaria Journal, 6, pp. 1–6. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2883-6-7.

NIHRD (2019) The 2018 Indonesia Basic Health Survey (Riskesdas): National Report. Jakarta: National Institute of Health Research and Development of The Indonesia Ministry of Health.

Ogbonnaya, L.U. and Okeibunor, J.C. (2004) ‘Sociocultural Factors Affecting the Prevalence and Control of Lymphatic Filariasis in Lau Local Government Area, Taraba State', International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 23(4), pp. 341–371. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2190/AY5A-QAY4-6H8D-VEL7.

Oktarina, R. (2010) Faktor-Faktor Yang Berhubungan Dengan Praktek Minum Obat Pada Pengobatan Massal Filariasis Di Kelurahan Sukajadi Kabupaten Banyuasin Tahun 2009. Universitas Indonesia.

Purwantyastuti (2010) ‘Pemberian Obat Massal Pencegahan (POMP) Filariasis', Buletin Jendela Epidemiologi, 1(1), pp. 15–20.

Santhi, F. (2011) Kepatuhan Minum Obat Filariasis Pada Pengobatan Massal Berdasarkan Teori Health Belief Model Di Kelurahan Limo Depok Tahun 2011. Universitas Indonesia.

Sari, P.R., Ginandjar, P. and Saraswati, L.D. (2020) ‘Gambaran Kepatuhan Minum Obat Pencegahan Massal Filariasis (Studi Di Wilayah Kerja Puskesmas Jetak Kabupaten Semarang', Jurnal Kesehatan Masyarakat (e-Journal), 8(4), pp. 463–468. Available at: https://ejournal3.undip.ac.id/index.php/jkm/article/view/26982.

Sartirano, D. et al. (2023) ‘Strengths and limitations of relative wealth indices derived from big data in Indonesia', Front Big Data., 6: 1054156. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fdata.2023.1054156.

Silumbwe, A. et al. (2017) ‘A systematic review of factors that shape implementation of mass drug administration for lymphatic filariasis in sub-Saharan Africa', BMC Public Health, 17(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4414-5.

Sindhu, K.N. et al. (2023) ‘Perceptions Associated with Noncompliance to Community-Wide Mass Drug Administration for Soil-Transmitted Helminths', American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 109(4), pp. 830–834. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.23-0176.

Suharmiati, S., Laksono, A.D. and Astuti, W.D. (2013) ‘Review Kebijakan tentang Pelayanan Kesehatan Puskesmas di Daerah Ter pencil Perbatasan', Bull Heal Syst Res., 16: 109–11. Available at: https://www.neliti.com/publications/20839/up-review-kebijakan-tentang-pelayanan-kesehatan-puskesmas-di-daerah-terpencil-pe.

Sungpradit, S. and Sanprasert, V. (2020) ‘Lymphatic filariasis', in G. Misra and V.K. Srivastava (eds) Molecular Advancements in Tropical Diseases Drug Discovery. London: Elsevier Inc., pp. 65–94. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420004946.ch8.

Taylor, M. et al. (2022) ‘Community views on mass drug administration for filariasis: a qualitative evidence synthesis', Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2022(2), pp. CD013638–CD013638. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013638.pub2.

Titaley, C.R. et al. (2018) ‘Assessing knowledge about lymphatic filariasis and the implementation of mass drug administration amongst drug deliverers in three districts/cities of Indonesia', Parasites and Vectors, 11(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-2881-x.

Widawati, M. et al. (2020) ‘Sociodemographic, Knowledge, and Attitude Determinants of Lymphatic Filariasis Medication Adherence in Subang, Indonesia', 24(94), pp. 1–6. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2991/ahsr.k.200311.001.

Widiastuti, D. et al. (2021) ‘Adverse reactions following mass drug administration with diethylcarbamazine and albendazole for lymphatic filariasis elimination in West Sumatera, Indonesia', Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health, 52(1), pp. 1–10. Available at: https://journal.seameotropmednetwork.org/index.php/jtropmed/article/view/381.

Widjanarko, B., Saraswati, L.D. and Ginandjar, P. (2018) ‘Perceived threat and benefit toward community compliance of filariasis' mass drug administration in Pekalongan district, Indonesia', Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 11, pp. 189–197. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S172860.

Won, K.Y. et al. (2009) ‘Assessing the Impact of a Missed Mass Drug Administration in Haiti', PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 3(8): e443. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000443.

World Bank (2020) ‘Total Population (2018). Public Data. [citation : 21 April 2020].'

Copyright (c) 2024 Agung Puja Kesuma, Mara Ipa, Agung Dwi Laksono, Tri Wahono, Rina Marina , Lukman Hakim

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

1. As an author you (or your employer or institution) may do the following:

- make copies (print or electronic) of the article for your own personal use, including for your own classroom teaching use;

- make copies and distribute such copies (including through e-mail) of the article to research colleagues, for the personal use by such colleagues (but not commercially or systematically, e.g. via an e-mail list or list server);

- present the article at a meeting or conference and to distribute copies of the article to the delegates attending such meeting;

- for your employer, if the article is a ‘work for hire', made within the scope of your employment, your employer may use all or part of the information in the article for other intra-company use (e.g. training);

- retain patent and trademark rights and rights to any process, procedure, or article of manufacture described in the article;

- include the article in full or in part in a thesis or dissertation (provided that this is not to be published commercially);

- use the article or any part thereof in a printed compilation of your works, such as collected writings or lecture notes (subsequent to publication of the article in the journal); and prepare other derivative works, to extend the article into book-length form, or to otherwise re-use portions or excerpts in other works, with full acknowledgement of its original publication in the journal;

- may reproduce or authorize others to reproduce the article, material extracted from the article, or derivative works for the author's personal use or for company use, provided that the source and the copyright notice are indicated.

All copies, print or electronic, or other use of the paper or article must include the appropriate bibliographic citation for the article's publication in the journal.

2. Requests from third parties

Although authors are permitted to re-use all or portions of the article in other works, this does not include granting third-party requests for reprinting, republishing, or other types of re-use.

3. Author Online Use

- Personal Servers. Authors and/or their employers shall have the right to post the accepted version of articles pre-print version of the article, or revised personal version of the final text of the article (to reflect changes made in the peer review and editing process) on their own personal servers or the servers of their institutions or employers without permission from JAKI;

- Classroom or Internal Training Use. An author is expressly permitted to post any portion of the accepted version of his/her own articles on the author's personal web site or the servers of the author's institution or company in connection with the author's teaching, training, or work responsibilities, provided that the appropriate copyright, credit, and reuse notices appear prominently with the posted material. Examples of permitted uses are lecture materials, course packs, e-reserves, conference presentations, or in-house training courses;