Predictive Factors of Time Die From COVID-19 in Intensive Care Units

To identify risk factors that increase or decrease the probability of dying from Covid-19 in Intensive Care Units (ICU) patients. This study is based on data collected retrospectively from the hospital records. The proportional model assumption was verified using the Kaplan–Meier method, and Cox Hazard Proportional Regression model to identify predictors' factors associated with time to death by Covid-19. Four factors were identified, two of them increase the probability of dying: age (Adjusted Hazard Ratio (HRa) = 1.032 (1.022–1.041), and breathing frequency HRa = 1.035 (1.016-1.054), and two decrease the probability: lymphocytes HRa = -0 815 (0.674–0.985), and diastolic pressure HRa = -0.992 (0.986–0.998). Every five years of increase in age the probability of dying does the same by 13.5%; while with an increase of three breaths there is an increase in the probability of dying equal to 7.4%. At the same time, five ml increase in mercury pressure will decrease mortality probability by 1.6%, while a 1.5 increase in lymphocytes will decrease it by 7.9%. Knowing these factors will undoubtedly be a useful tool to identify those patients who, due to their clinical condition, have a morbidity profile that classifies them as very high risk of dying, and therefore deserve personalized medical care.

INTRODUCTION

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, originating in the province of Wuhan, in China, became a great challenge for health systems in the world, mainly due to the most severe clinical form, characterized by a Syndrome of Acute respiratory failure, which usually leads quickly to death. According to the WHO, as of June 2022, more than 255 million cases have been registered, with more than 5 million deaths worldwide11. The Americas region had reported 165.428.595 million confirmed cases of Covid-19 with 2.769.969, for a case fatality rate of 1.7%. Almost a third, 30.6% of the cases and 10.6% of the deaths were reported between January and March 2022. The North and South American subregions had the highest proportion of cumulative cases, 59% and 37%, respectively, and 49% and 47% of deaths, as of June 202222.

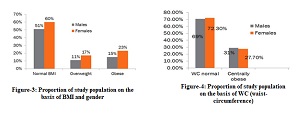

Colombia, on the same date, had reported 6.198.848 confirmed cases and 140.202 deaths, with a fatality rate of 2.3%. In the department of Valle del Cauca, as of June 2022, 551.933 cases and 15.119 deaths were registered, with a fatality rate of 2.7%33. Consequently, the scientific community has focused its interest on the identification of factors associated with the increase in the severity of the disease and death. Between 14% and 30% of hospitalized patients require Intensive Care Unit (ICU) care, and older age and male gender are factors reported to be associated with increased risk of ICU admission and high mortality4-1045678910.

A retrospective cohort study of critically ill patients in the ICU, in Lombardy, Italy, with laboratory-confirmed Covid-19, reported that the median length of ICU stay was 12 days, with a range from six to 21 days1111. A Meta-Analysis study found that chronic comorbidities, such as acute kidney injury, COPD, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and increased D-dimer, and demographic variables such as male gender, older age, current smoking, and obesity are risk factors that increase the probability of a fatal outcome associated with the coronavirus in the ICU1212.

A retrospective cross-sectional study from a single center in Palmira, Colombia, reported risk factors that predict hospital mortality, due to Covid19, such as elevated levels of lactate dehydrogenase and high-sensitivity troponin I, acute renal failure, COPD and > 10 points in the MuLBSTA score; also need invasive mechanical ventilation in patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia1313. Great efforts have been made to identify the predictors of mortality from Covid-19 in critically ill patients hospitalized in the ICU, to implement early therapeutic protocols to reduce lethality. Although some factors have been reported in the scientific literature, these factors are still not well known in Colombia. This study aimed to identify some predictors of mortality from Covid-19 in patients hospitalized in Intensive Care Units (ICU) in a medium and high complexity hospital.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective cohort study carried out with patients hospitalized for Covid-19, in the ICU of the Tomas Uribe Uribe departmental hospital of medium and high complexity in Tulua, Colombia. The number of patients hospitalized in the ICU with Covid-19 from April 1, 2020, to July 31, 2021, was 2.328, of which 1,468 were due to Covid-19, of which 895 were men. Among patients with Covid-19, 730 died from this cause, 456 men (62.5%), and 14 records were excluded for having incomplete data. Those patients over 15 years of age who had at least one record of a positive RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 and sufficient data (>80%) on the variables of interest were included. The endpoint of interest was death from Covid-19.

Source of data. Data collected from the institutional information system were: heart and respiratory rate, diastolic and systolic pressure, D-dimer, hemoglobin, hematocrit, neutrophils, lymphocytes, leukocytes, oxygen saturation, age, sex, weight, height, date of admission and discharge from the ICU, condition at discharge from the ICU (alive or dead). Numerical errors, such as multicollinearity, were reviewed to avoid inaccurate estimates; Collinearity was considered when the Pearson correlation coefficient was greater than 0.80, and none of the variables examined showed collinearity. The presence of complete separation and cells with zero observations were also checked. For the cell count, the logarithmic function was used, that is, they were included in the model in the form of a logarithm.

Statistical analysis. Data were collected and tabulated for statistical analysis in an Excel® spreadsheet. Quantitative data, continuous or not, were presented using mean and standard deviation (SD) and the age variable in tertiles because of its distribution was skewed towards older age groups. Categorical data were presented as number, and percentages. To evaluate the assumption of proportionality, perhaps the most important assumption when using the Cox proportional model, the Kaplan-Meier (KM) method13-15131415was applied to all the independent variables or predictors. Another way to test the proportionality assumption is to use the residuals1616.

Statistical significance was assessed using the Log-Rank statistical test, which gives equal weight to the variables throughout the series and, therefore, is very powerful in detecting differences that have a constant relative risk. Variables with a probability equal to or greater than 0.10 were excluded from the Cox proportional analysis. Cox Proportional Regression Model13-15131415, was used, with the stepwise option, to identify the predictive factors that increase or decrease the probability of dying from Covid-19 in ICU, the

WHO Director-General´s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-mediabriefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020. Accessed April 1.

Geo-Hub Covid19. Information System for the Region of the Americas. PAHO, July 2022.

Secretaria Departamental de Salud. Valle del Cauca. Junio 2022.

Assal et al. The Egyptian Journal of Bronchology (2022) 16:18 https://doi.org/10.1186/s43168-022-00122-0

J. Yang et al. / International Journal of Infectious Diseases 94 (2020) 91–95doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017.

Guan W-j, Liang W-h, Zhao Y, et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 2000547 [https://doi.org/10.1183/ 13993003.00547-2020].

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. WWW.The Lancet.com 2020; 395:1054–1062. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3.

Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford J, Thomas M, Davidson K, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5,700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA 2020;323:2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775.

Myers LC, Parodi SM, Escobar GJ, Liu VX. Characteristics of hospitalized adults with COVID-19 in an integrated health care system in California. JAMA 2020; 323:2195–2198. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7202.

Hobbs ALV, Turner N, Omer I, Walker M, Beaulieu R, Sheikh M, et al. Risk factors for mortality and progression to severe COVID-19 disease in the Southeast region in the United States: A report from the SEUS Study Group. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology (2021), 42, 1464–1472 doi:10.1017/ice.2020.1435

Grasselli G, Greco M, Zanella A, Albano G, Antonelli M, Bellani G, et al. Risk Factors Associated With Mortality among Patients With COVID-19 in Intensive Care Units in Lombardy, Italy. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1345-1355.doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3539.

Parohan M, Yaghoubi S, Seraji A, Javanbakht MH, Sarraf P, Djalali M. Risk factors for mortality in patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. 23(5):1416-1424, The Aging Male, 2020 https://doi.org/10.1080/13685538.2020.1774748.

Esteban Ronda V, Ruiz Alcaraz S, Ruiz Torregrosa P, Giménez Suau M, Nofuentes Pérez E, León Ramírez JM, et al. Aplicación de escalas pronósticas de gravedad en la neumonía por SARS-CoV-2. Med Clin (Barc). 2021; 157:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2021.01.002

2387-0206/© 2021 Elsevier Espa ̃na, S.L.U. All rights reserved.Elisa T. Lee. Statistical Methods for Survival Data Analysis. Second edition. New York. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1992; pp 233-314.

A. Gouveia Oliveira. Biostatistics Decoded. Singapore. Markano Print Media Pte Ltd, 2013; pp 219-227.

Chap T. Lee. Analysis of survival analysis data and data from matched studies. En: Introductory Biostatistics. Hoboken, New Jersey. John Wiley & Sons Publication, 2003. Pp 379-444.

Schoenfeld D. Partial residuals for the proportional hazards regression model. Biometrika, 1982;69(1):239– 241. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S2667-193X(22)00114-4/sbref0024https://doi.org/10.2307/2335876.

SAS Institute Inc., SAS 9.4. Applications based on SAS software, 2021.

J.A. Cortes et al. / Infection Prevention in Practice 5 (2023) 100283 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infpip.2023.100283

Assal HH, Abdel-hamid H, Magdy S, Salah M, Ali A, Elkaffas RH, Sabry IM. Predictors of severity and mortality in Covid-19 patients. The Egyptian Journal of Bronchology. (2022) 16:18 https://doi.org/10.1186/s43168-022-00122-0.

Dessie ZG, Zewotir T. Mortality‑related risk factors of COVID‑19: a systematic review and meta‑analysis of 42 studies and 423,117 patients. BMC Infectious Diseases (2021) 21:855 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06536-3.

Chen Y, Liu Z, Li X, Zhao J, Wu D, Xiao M, et al. Risk factors for mortality due to COVID-19 in intensive care units: a single-center study. Ann Transl Med, 2021;9(4):276 | http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-4877.

Hergens MP, Bell M, Haglund P, Sundström J, Lampa E, Nederby-Öhd J, et al. Risk factors for COVID‑19‑related death, hospitalization and intensive care: a population‑wide study of all inhabitants in Stockholmo. European Journal of Epidemiology (2022) 37 (2):157–165 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-021-00840-7.

Haschka D, Petzer V, Burkert FR, Fritsche G, Wildner S, Bellmann-Weiler R et al. Alterations of blood monocyte subset distribution and surface phenotype are linked to infection severity in COVID-19 inpatients. Eur. J. Immunol. 2022. doi: 10.1002/eji.202149680.

Parohan M, Yaghoubi S, Seraji A, avanbakht MH, Sarraf P, Djalali. Risk factors for mortality in patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Aging Male 2020, 23 (5), 1416–1424 https://doi.org/10.1080/13685538.2020.1774748

Copyright (c) 2024 Gustavo Bergonzoli, Felipe Jose Tinoco Zapata, Carolina Jaramillo, Christian Jhoan Rodriguez

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

- The journal allows the author to hold the copyright of the article without restrictions.

- The journal allows the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.

- The legal formal aspect of journal publication accessibility refers to Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike (CC BY-SA).

- The Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike (CC BY-SA) license allows re-distribution and re-use of a licensed work on the conditions that the creator is appropriately credited and that any derivative work is made available under "the same, similar or a compatible license”. Other than the conditions mentioned above, the editorial board is not responsible for copyright violation.