Epidemiological, Clinical, Bacteriological, and Therapeutic Aspects of Sur-gical Site Infections in the Maternity Ward of the Batna Region, Algeria: A Prospective Study

Surgical site infections (SSIs) are nosocomial infections occurring after surgery. SSIs contribute to the increase in maternal morbidity associated with cesarean section (CS). This research aimed to study SSIs' clinical, epidemiological, bacteriological, and therapeutic aspects for cesarean and hysterectomy surgeries performed at the Maternity Hospital of Batna Region in Algeria. We carried out a prospective and descriptive study for four months (from 1 January 2018 to 30 April 2018), with real-time data collection, in the gynecology and obstetrics department of Batna’s Maternity Hospital. We included a total of 24 women who had a surgical intervention and were hospitalized with post-surgical infection. The data collection using a questionnaire allowed us to obtain information concerning the patient and the surgical procedure. Our results show that most surgeries performed were CS (95.83%) compared to hysterectomies (4.16%), among which 54.16% were planned CS. All classes of contamination were clean-contaminated. The physical status score for American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) 1 and ASA 2 classes was found in 83.33% and 16.66% of the patients, respectively. The SSIs in this study were concerned mainly with the surface plane (95.83%). Concerning infection, pus samples were taken from ten patients, and five germs were identified in eight patients. Escherichia coli was isolated in three patients, and Proteus mirabilis in two patients. Serratia marcescens, Acinetobacter baumanni, and Burkholderia cepacia were identified once in the three remaining patients. The most commonly prescribed antibiotherapy was Metronidazole (95.83%). We established a clinical, epidemiological, bacteriological, and therapeutic profile for SSIs at the Maternity Hospital of Batna.

INTRODUCTION

Surgical site infections (SSIs) include any infection at the operated site occurring within 30 days of surgery or a year if an implant or prosthesis has been placed11. Caesarean section (CS) is a lifesaving operative technique in which a fetus, placenta, and membranes are delivered through an abdominal and uterine incision22. A survey revealed that caesarean section procedures carry a risk of infection 5–20 times that of normal delivery33. SSIs constitute a significant public health problem and remain one of the leading causes of mortality and morbidity in surgery.

There are many risk factors for SSIs associated with cesarean section; the main risk factors involved are the pre-, per-, and postoperative environment surrounding the patient and the healthcare team, the host’s immune defences, and especially the degree of hygiene during the surgical act. In the relentless pursuit of averting surgical site infections, a two-pronged approach unfolds, centering on identifying risk factors that collectively fall into two distinctive categories: patient-related (intrinsic) and process/procedural-related (extrinsic) factors. These risk factors, whether modifiable or non-modifiable, constitute pivotal keystones in the campaign for infection prevention44. Understanding the interplay between these factors is crucial for developing comprehensive strategies to reduce the incidence of SSIs.

The diagnosis of SSIs is essentially clinical; however, the etiological diagnosis requires the isolation of a bacterium after a culture of the purulent fluid is taken55. Bacteria inoculated into the surgical site during surgery typically cause SSIs.E. coliandEnterococcusspecies, respectively, cause approximately 9.5%and 5.1% of all surgical site infections66. Pathogens that cause infection vary by surgical location. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for caesarean section effectively reduces postoperative morbidity, cost, and duration of hospitalization22.

SSIs are the second most reported healthcare-associated infection (HAI) globally, accounting for 19.6% of HAIs77. Numerous studies have reported incidence rates of post-CS SSIs, for example, 2.85% in India88, 21% in Ethiopia33, and in Blantyre, Malawi. The overall cumulative incidence of SSI recorded at the Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital during the study period was 9.61% (20 cases out of 208). Of these, 19 (95%) reported superficial SSI following CS22. The developing countries are the most affected. In Algeria, the incidence surveys were carried out in some hospitals, as Annaba’s hospital had 36 (1.9%) post-CS SSIs among 1,810 patients99.

This study was conducted to determine the clinical, epidemiological, bacteriological, and therapeutic profile of surgical site infections for caesarean and hysterectomy surgeries performed at the Maternity Hospital of Batna and to identify risk factors for SSI after caesarean section for 4 months (from January 1, 2018 to April 30, 2018). A better understanding of predictors might improve infection control by reducing the clinical effects of post-cesarean infections. To our knowledge, no epidemiological study has been conducted on SSIs at the maternity hospital of Batna. This work is the first to study these different aspects of SSIs at this establishment.

METHODS

Patients and methods

This prospective and descriptive study was conducted in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Hospital Maternity of Batna Region in Algeria. The analysis of files was spread over 4 months (from 1 January 2018 to 30 April 2018), including 24 women who underwent surgery such as caesarean delivery or hysterectomy during this period and were hospitalized at the Maternity Hospital. SSI diagnosis was established according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) criteria of Atlanta10,111011, and the surgeon validated each SSI. For bacteriological analysis, a pus sample was taken for superficial and deep infections to detect the eventual presence of microorganisms (bacteria).

Data collection

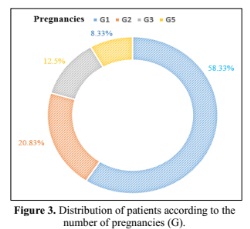

The data were collected by analysis of medical records in the obstetrics-gynecology department (data were provided anonymously by the hospital services). The data collection using a questionnaire allowed us to obtain information concerning the patient, such as age, level of education, profession …etc, and information concerning the surgical procedure: the type of surgery, the emergency or programmed intervention, the number of pregnancies (G), the epidemiological and bacteriological characteristics (classe of contamination, infection site, presence of germs), the associated risk factors and length of stay. We have performed a descriptive statistical analysis of all our patients’ epidemiological and clinical characteristics.

Inclusion criteria

The recruitment was done exhaustively: systematic inclusion of all:

- Parturients who have had an emergency or planned caesarean section, for any indication.

- Primiparous or multiparous (including those who have already had a previous cesarean).

Exclusion criteria

We have excluded all of the following:

- Parturients who have given birth vaginally.

- Parturients transferred to the obstetrics-gynecology department in the postpartum period after a cesarean section performed in another establishment.

The limits of the study

Our study experienced limitations for the following reasons:

- Pus collection was not systematic for all patients.

- The operative reports were incomplete.

Statistical Analysis

This work addressed a descriptive statistical study. It evaluated the prevalence of different parameters and factors, and the results are expressed as frequency and percentage.

RESULTS

In our series, the mean age of our patients was (28.71 ± 7.049) years, with extremes of 19 and 52 years. Surgical site infections are frequent in the age group of 26-35 years (Table 1). Our results show a higher proportion, or 91.66%, of women with a good level of education.

Chalfine A. Prévention et surveillance des infections du site opératoire. Prat En Anesth Réanimation. avr 2004; 8(2): 156-65. DOI : 10.1016/S1279-7960(04)98185-5

Kachipedzu AM, King DI, Meja SJ and Musaya. Surgical site infection and antimicrobial use following caesarean section at QECH in Blantyre, Malawi: a prospective cohort study. 2024. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control (2024) 13:131. DOI : DOI: 10.1186/s13756-024-01483-5

Azeze GG, Bizuneh AD. Surgical site infection and its associated factors following caesarean section in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):1–6. DOI: 10.1186/s13104-019-4325-x

Bucataru A , Balasoiu M ,Ghenea AE , Zlatian OM ,Vulcanescu DD , Horhat FG, Bagiu LC, Sorop VB, Sorop ML, Oprisoni A , Boeriu E and Mogoanta SS. Clin. Pract. 2024, 14, 52–68. DOI: 10.3390/clinpract14010006

Julie NMME, Miabaou DM,Tsouassa Wa Ngono GB, Ontsira Ngoyi EN, Ossibi PE, Monwongui BM, Avala PP, Latou NMH, Moukala CN. Les Infections du Site Opératoire en Chirurgie Digestive à Brazzaville. Health Res. Afr. 2024; Vol 2 (3) pp 58-63 https://hsd-fmsb.org/index.php/HRA/article/view/5425

Seidelman JL, Baker AW, Lewis SS, Advani SD, Smith B, Anderson D; Duke Infection Control Outreach Network Surveillance Team. Surgical site infection trends in community hospitals from 2013 to 2018. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2023; Apr;44 (4):610-615. DOI: 10.1017/ice.2022.135

Allegranzi B, Pittet D. Preventing infections acquired during healthcare delivery. Lancet. 2008;372(9651):1719–20. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61715-8

Njoku CO, Njoku AN. Microbiological pattern of surgical site infection following caesarean section at the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital. Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7(9):1430. https://oamjms.eu/index.php/mjms/article/view/oamjms.2019.286

Boutefnouchet C, Aouras H, Khennouchi NCEH, Berredjem H , Rolain JM, Hadjadj L. Algerian postcaesarean surgical site infections: A cross-sectional investigation of the epidemiology, bacteriology, and antibiotic resistance profile. Am J Infect Control. 2024 Apr;52(4):456-462. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajic.2023.09.022

National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Report, Data report from January 1992-June 2001, issued Auguste 2001. Am J Infect Control 2001; 29 (6): 404-21. DOI: 10.1067/mic.2001.119952

Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG. CDC definitions of surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.1992; 13 (10): 606-8. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/infection-control-and-hospital-epidemiology/article/abs/cdc-definitions-of-nosocomial-surgical-site-infections-1992-a-modification-of-cdc-definitions-of-surgical-wound-infections/560CF81A0BAA16EFA0E6066B1F3516ED

Jasim HH, Sulaiman SAS, Amer Hayat Khan, Dawood OT, Hadi AA and R Usha. Incidence and Risk Factors of Surgical Site Infection Among Patients Undergoing Cesarean Section. Clinical Medicine Insights: Therapeutics 2017; Volume 9: 1–7.doi : Clinical Medicine Insights: DOI : 10.1177/1179559X17725273

Barbut F, Carbonne B, Truchot F, Spielvogel C, Jannet D, Goderel I, Lejeune V, Milliez J. (2004). Infections de site opératoire chez les patientes césarisées : bilan de 5 années de surveillance. Journal de Gynécologie Obstétrique et Biologie de la Reproduction. 2004; (33) 6: 487-496. DOI: 10.1016/s0368-2315(04)96561-1

Jarlier V. Bacteries multi resistantes dans les hopitaux francais: des premiers indicateurs au Réseau d'alerte d'investigation et de surveillance des infections nosocomiales (RAISIN). Bulletin Epidémiologique Hebdomadaire. 2004;32-33:148-51. https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/maladies-et-traumatismes/infections-associees-aux-soins-et-resistance-aux-antibiotiques/resistance-aux-antibiotiques/documents/article/bacteries-multiresistantes-dans-les-hopitaux-francais-des-premiers-indicateurs-au-reseau-d-alerte-d-investigation-et-de-surveillance-des-infectio

Ngaroua, Ngah JE, Bénet T, Djibrilla Y. Incidence des infections du site opératoire en Afrique sub-saharienne: revue systématique et méta-analyse. Pan African Medical Journal. 2016; 24:171. DOI: 10.11604/pamj.2016.24.171.9754.

Ngowa JDK, Ngassam A, Mbouopda RM, Kasia JM. (2014). Antibioprophylaxie dans les chirurgies gynécologiques et obstétricales propre et propres contaminées à L’Hôpital Général de Yaoundé, Cameroun. Pan Afr Med J. 2014; 19: 23. DOI: 10.11604/pamj.2014.19.23.4534

Donowitz LG, Wenzel RP. Endometritis following caesarean section. A controlled study of the increased duration of hospital stay and direct cost of hospitalization. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;137:467–9. DOI: 10.1016/0002-9378(80)91130-8

Litta P, Vita P, de Toffoli J Konishi, Onnis GL. Risk factors for complicating infections after caesarean section. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 1995;22:71–5. https://europepmc.org/article/med/7736646

Beattie PG, Rings TR, Hunter MF, Lake Y. Risk factors for wound infection following caesarean section. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;34:398–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1994.tb01256.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1994.tb01256.x

Alseny-Gouly C, Botherel A-H, Lebascle K, Daniel F, Astagneau P. Les facteurs de risque des infections du site opératoire après césarienne « étude cas témoins». Revue d'Epidémiologie et de Santé Publique. 2008; 56 (5): 260. DOI : 10.1016/j.respe.2008.06.027

Jido TA and Garba ID. Surgical-site Infection Following Cesarean Section in Kano, Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2012 ; 2(1): 33–36. https://www.amhsr.org/articles/surgicalsite-infection-following-cesarean-section-in-kano-nigeria.html

Ezechi OC, Nwokoro CA, Kalu BK, Njokanma FO, Okeke GC. Caesarean section: Morbidity and mortality in a private hospital in Lagos Nigeria. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002; 19:97–100. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/tjog/article/view/14382

Saeed K Bm, Corcoran P, O'Riordan M, Greene RA. Risk factors for surgical site infection after cesarean delivery: A case-control study. Am J Infect Control. 2018; 47(2):164-169. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.07.023.

Mpogoro FJ , Mshana SE , Mirambo MM , Kidenya BR , Gumodoka B , Imirzalioglu C. Incidence and predictors of surgical site infections following caesarean sections at Bugando Medical Centre, Mwanza, Tanzania. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2014; 3 (1): 25. doi :10.1186/2047-2994-3-25. DOI: 10.1186/2047-2994-3-25

Tang R, Chen HH, Wang YL, Changchien CR , Chen JS, Hsu KC, Chiang JM, Wang JY. Risk factors for surgical site infection after elective resection of the colon and rectum: a single-center prospective study of 2,809 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2001; 234(2):181-9. DOI: 10.1097/00000658-200108000-00007

Brahimi G, Slaouti S. Surveillance of surgical site infections at the rhinolaryngology department of BENI MESSOUS UNIVERSITY in 2019. Journal of Xi'an Shiyou University, Natural Sciences Edition. 2024 ; Vol: 67 Issue 04.

DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.11031766 https://xianshiyoudaxuexuebao.com/dashboard/uploads/12.11031766.pdf.

Ouédraogo E . 15-2 - Les infections du site opératoire après césarienne en urgence au Centre hospitalier universitaire de Bogodogo, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Journal of Epidemiology and Population Health. 2024; Vol 72 - N° S3 Article 202622- juillet 2024. DOI: 10.1016/j.jeph.2024.202622

Chadli M, Rtabi N, Alkandry S, Koek J, Achour A, Buisson Y, Baaj A. Incidence of surgical wound infections a prospective study in the Rabat Mohamed –V military hospital, Morocco.2005. Med Mal Infect; 35(4):218-22. DOI : 10.1016/j.medmal.2005.03.007.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Antibiotic prophylaxis in surgery. Edinburgh: SIGN. 2008. https://medicinainterna.net.pe/images/guias/GUIA_PARA_LA_PROFILAXIS_ANTIBIOTICA_EN_CIRUGIA.pdf

Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection. 1999. DOI: 10.1086/501620

Arias CA, Quintero G, Vanegas BE, Rico CL, Patiño JF. Surveillance of Surgical Site Infections: Decade of Experience at a Colombian Tertiary Care Center. World J Surg. 2003; 27(5):529-533. DOI : 10.1007/s00268-003-6786-1

Ouédraogo AS, Somé DA, Dakouré PWH, Sanon BG, Birba E, Poda GEA, Kambou T. Profil bactériologique des infections du site opératoire au centre hospitalier universitaire Souro Sanou de Bobo Dioulasso. Med Trop.2011; 71 (1):49-52. https://www.lissa.fr/rep/articles/21585091

Kumar TVR, Anand Goud K. A study of surgical site infections in a general practice hospital. International Surgery Journal. Int Surg J. 2019 ; Nov;6(11):4043-4047. DOI: 10.18203/2349-2902.isj20195120

Weinstein RA, Gaynes R, Edwards JR. Overview of nosocomial infections caused by gram-negative bacilli. Clin Infect Dis. 2005; 41 (6): 848-854. DOI: 10.1086/432803.

Raymond DP, Pelletier SJ, Crabtree TD, Evans HL, Pruett TL, Sawyer RG. Impact of antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacilli infections on outcome in hospitalized patients. Crit Care Med. 2003; 31 (4): 1035-1041. DOI: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000060015.77443.31.

Mukagendaneza MJ, Munyaneza E, Muhawenayo E, Nyirasebura D, Abahuje E, Nyirigira J, Harelimana JDD , Muvunyi TZ , Masaisa F , J Byiringiro JC, Hategekimana T , Muvunyi CM (2019). Incidence, root causes, and outcomes of surgical site infections in a tertiary care hospital in Rwanda: a prospective observational cohort study. Patient Safety in Surgery.2019 ; 13(1). DOI: 10.1186/s13037-019-0190-8.

Sievert DM, Ricks P, Edwards JR, Schneider A, Patel J, Srinivasan A, Kallen A, Limbago B, Fridkin S. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections : Summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009-2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013; 34:1-14. DOI: 10.1086/668770.

Misteli H, Widmer AF, Rosenthal R, OertliD, Marti WR, Weber WP. Spectrum of pathogens in surgical site infections at a Swiss university hospital. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;140:w13146. DOI: 10.4414/smw.2011.13146.

Seidelman JL, Mantyh CR, Anderson DJ. Surgical Site Infection Prevention : A Review. JAMA. 2023; 329(3):244-252. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2022.24075

Latham R, Lancaster AD, Covington JF, Pirolo JS, Thomas CS. The association of diabetes and glucose control with surgical-site infections among cardiothoracic surgery patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22:607-12. DOI: 10.1086/501830.

Vilar-Compte D , Alvarez de Iturbe I, Martín-Onraet A, Pérez-Amador M, Sánchez-Hernández C, Volkow P. Hyperglycemia as a risk factor for surgical site infections in patients undergoing mastectomy. Am J Infect Control. 2008 Apr;36(3):192-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.06.003.

Myles TD, Gooch J, Santolaya J. Obesity as an independent risk factor for infectious morbidity in patients who undergo cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2002; 100(5 Pt 1): 959-964. DOI: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02323-2.

AÇAR S, YILMAZER B, ÇİFTÇİ E, KUMRU P.Retrospective analysis of surgical site infections after cesarean section: Rates, microbiological profile, and clinical features. Zeynep Kamil Med J. 2022;53(1):8–16. DOI: 10.14744/zkmj.2022.71224

Minchella A, Alonso S, Cazaban M, Lemoine M C, Sotto A. Surveillance des infections du site opératoire en chirurgie digestive. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses.2008; 38 (9): 489-494. DOI: 10.1016/j.medmal.2008.06.012.

Leaper DJ, Edmiston CE.World Health Organization: global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection. J Hosp Infect. 2017;95(2): 135-136. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.12.016

Ban KA, Minei JP, Laronga C, et al. American College of Surgeons and Surgical Infection Society: surgical site infection guidelines, 2016 update. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224(1):59-74. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.10.029

Berrios-Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW, et al; Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection, 2017. JAMA Surg. 2017;152 (8):784-791. DOI: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0904

Nichols RL. Surgical antibiotic prophylaxis. Med Clin North Am. 1995; 79(3): 509-22. DOI: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30053-0

Cisse CT, Coly S, Akpaki F, Ewagnignon E, Dionne P, Faye EO, Diallo D, Sangare M, Moreau JC, Diadhiou F. Antibioprophylaxie à la carte en chirurgie gynécologique et obstétricale propre contaminée: intérêt du cefotaxime. Dakar Médical. 1997; 42(2): 127-131. https://europepmc.org/article/med/9827135

Lepelletier D, Bourigault C, Roussel JC, Lasserre C, Leclère B, Corvec S, Pattier S, Lepoivre T, Baron O, Despins P. Epidemiology and prevention of surgical site infections after cardiac surgery. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses. 2013; 43(10): 403–409. DOI: 10.1016/j.medmal.2013.07.003

Ikeanyi UOE, Chukwuka CN, Chukwuanukwu TOG. Risk factors for surgical site infections following clean orthopaedic operations. Niger J Clin Pract. 2013;16(4):443. DOI: 10.4103/1119-3077.116886

Copyright (c) 2025 Hayat DJAARA, Chahrazad charif , Chahra zed Benbrahim

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

- The journal allows the author to hold the copyright of the article without restrictions.

- The journal allows the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.

- The legal formal aspect of journal publication accessibility refers to Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike (CC BY-SA).

- The Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike (CC BY-SA) license allows re-distribution and re-use of a licensed work on the conditions that the creator is appropriately credited and that any derivative work is made available under "the same, similar or a compatible license”. Other than the conditions mentioned above, the editorial board is not responsible for copyright violation.